by The Curious Scribbler

It is very easy to overlook St Michael’s Church, Tremain. Tremain is a parish spread on either side the main road, a little north of Cardigan. There is no distinct village, just an erratic scatter of houses, and the church is out of sight, just off the main road to the south side, on a single track lane with high banks and no parking. Even to turn around having found it involves a muddy drive to the point where a concrete track leads on into a farmyard.

Little wonder then that the diocese eventually concluded that St Michael’s Tremain was superfluous to requirements.

This though is not to say it is without merit and it is tremendous news that thanks to the representations of local and national experts the church has been adopted by that estimable charity, The Friends of Friendless Churches, and the scaffolding has already gone up in anticipation of its restoration.

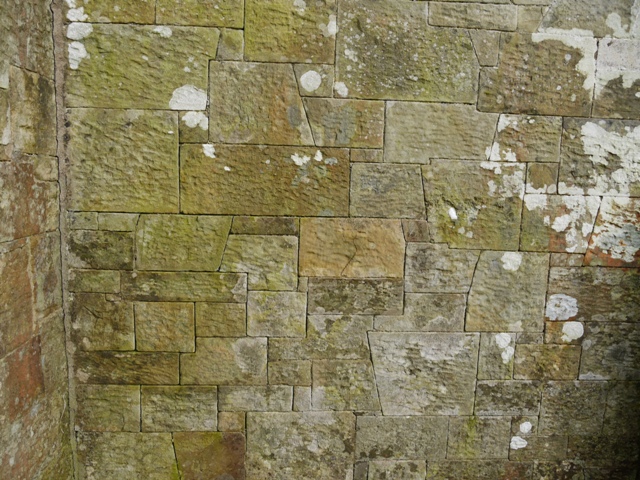

St Michael’s is a replacement church, built on an ancient site in 1846-8, and its architect was the famous Welsh bard John Jones ‘Talhaiarn’. The architectural style is ‘ecclesiologically correct’ (which I believe means conforming to the architectural rules devised by The Cambridge Camden Society), the decor is extremely plain with plastered walls and ceiling in an open rafter roof. There is a schoolroom vestry on one side of the nave fitted out with child-sized pews. But the most remarkable feature of the church is its masonry. Built of the local sandstone, Pwntan stone, the blocks have been each carefully shaped to create an intricate fit with their neighbours. So close is the fit that mortar looks to have been almost superfluous, and rather than being a structure of coursed blocks, the whole external surface of the church resembles a complex jigsaw puzzle in which no two pieces are even similar.

John Jones, a joiner’s son, was born in 1810 and at the age of 15 he was apprenticed to an architect named Ward, who was superintending the building of Pool Park, Ruthin for Lord Bagot. By 1843 he worked for the ecclesiastical architects Scott and Moffatt of London, and in 1851 he left them to work for Sir Joseph Paxton as a superintendent of the building of the Crystal Palace, and of a mansion for Baron Meyer de Rothschild near Menton, France. But there is no evidence that in any of these projects was the masonry fitted together in the obsessionally eccentric way it was built at Tremain.

The identity of the Tremain mason is unknown, and if it were a personal whim of his it is not a building style he seems to have employed in other buildings locally. Oddly, the best echo of this construction is in the work of 13th to 15th century Inca masons in Peru! Here too, blocks were individually fitted together, with neat edges and corners to complement the adjoining stones. Often Inca building involved massive stones in defensive walls, on a far larger scale than in the church.

John Jones’ other, and more celebrated, life was as a poet. Under the name ‘Talhaiarn’ he published a number of volumes in Welsh between 1849 and 1869, when he died by his own hand. According to Welsh Biography Online ‘his fame rests mainly on his songs and light verse, often satirical.’ There is presently no clue as to the inspiration for the unique stonework of this small Welsh Church. It is an architectural curiosity of the first order.

http://www.friendsoffriendlesschurches.org.uk The Friends own twenty architecturally and historically important churches in Wales, where their restoration is funded by Cadw and the Church in Wales.

The local expert on Tremain church is Brenda Howells: e mail: brenda@owlscote.com