by The Curious Scribbler

Walking along Queen’s Road these days one finds a strangely discordant sight, the 19th century Catholic Church, St Winefride’s, has suddenly found itself encased in security fencing and strident site warning signs. Which is odd because the building is pleasing to look upon, with well tended lawns and a pretty Presbytery House, occupied until just a few months ago, which is framed in roses and hydrangeas. It has always made an uplifting scene in this Conservation Area of Aberystwyth, the only building which is well set back, providing a green oasis of lawn.

Intimidating security fences have appeared around St Winefride’s Church

But all is not well in this idyllic spot, for the Catholic Bishop of Menevia is set upon dispensing with this church, much to the dismay of many of the parishioners, for whom it is of personal and cultural importance. That very lawn is perhaps the key to its undoing, for the site of house, church and garden would accommodate a lucrative development of flats – (what is described in the application as a ‘Quality Mixed Residential Development’). The Bishop plans to bring in the wrecking ball and demolish the lot.

The Presbytery and its pretty garden will be neglected until demolition can be secured.

The Council Planning Department however opposes the demolition of much-loved buildings in a Conservation Area, and the legislation suggests that before this course of action can be considered the owner must put the building up for sale to establish whether an alternative use can be found. And so it is shortly to be put up with a local Agent. Now, while most people trying to sell a slightly shabby but charming building would try to emphasise its best points, it seems the Church has other ideas. The security fencing is an eyesore, and erected as it is upon the lawn, the garden will soon be overgrown and ugly too. The best outcome from the Bishop’s point of view would be to demonstrate that no buyer will match their price, and then re-apply for demolition.

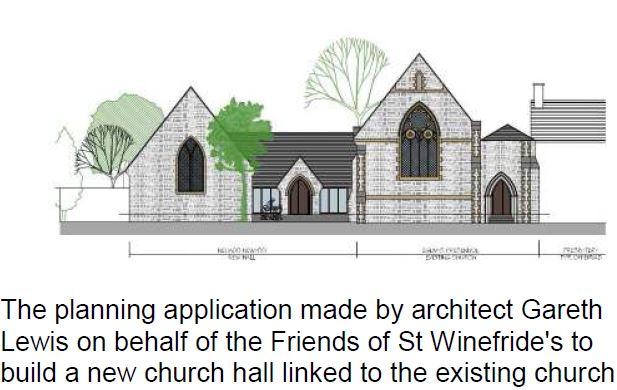

The parishioners meanwhile have not been idling. The Save St Winefride’s campaign has funded surveyors to consider the realistic costs of repairing a sound but somewhat elderly building, and have drawn up plans to renovate the buildings and build an additional Church Hall upon the site. This design is unpretentious, sympathetic, and has been granted Planning Permission by the County Council. The whole project would cost £1.2 million, far less than the £2.7 million estimated by the Bishop’s architects for their impossibly expensive version of the job.

So why not accept the wishes of the congregation? The Bishop has an alternative plan, first promoted in 2008, centred upon a little-known ruin two miles from the town centre in the suburb of Penparcau. Here is another Church, the far more neglected Welsh Martyrs. A brutalist concrete structure from 1968, it has been closed for many years. Few people have even noticed it, for it is down a side road near the Tollgate public house. The new Pevsner described is as “an interesting design, let down by poor finish and detail”. The Bishop wants to pull that down too, and with more justification.

The derelict church of Welsh Martyrs, Penparcau. Photographed by Paul White, http://www.welshruins.co.uk/photo14087508.html#photo

You could, alternatively, put a block of flats here, but Penparcau is not as sought-after as the town centre, the site is less valuable, and the profits would doubtless be less. Instead, the vision is that Catholic worshippers from the town will take one of the rare Sunday buses out to Penparcau and walk down to a newly-built modernist building on the Welsh Martyrs site. It is hard to imagine that this will be a popular choice with worshippers. University students, who include many foreign Catholics will have a yet more daunting journey from their halls of residence on the opposing hill. Townsfolk who have been hatched, matched and dispatched at Queen’s Road for generations would like to go on doing so.

The repercussions continue from a well organised parishioner and community action group which has become more active and vociferous as it has found its views to be ignored by the Church. There have been representations to the Vatican, consultations on Canon Law, opposing teams of surveyors and valuers, a sit-in in the church, an offer of resignation from the Board of Trustees by the incumbent priest. The Diocese of Menevia, though, is a vast catholic administrative region – stretching right down to Swansea. Angry Aberystwyth must seem very insignificant to a property-developer Bishop.

For much more detail visit http://savestwinefrides.co.uk/home.html which gives links to a Dropbox bulging with damning evidence of manipulation behind the scenes.