by The Curious Scribbler

Following last week’s blog I have had a most informative communication from Tom Lloyd, renowned bibliophile and Wales Herald of Arms. His comments raise questions: for whom and for what purpose was this embellished crest engraved?

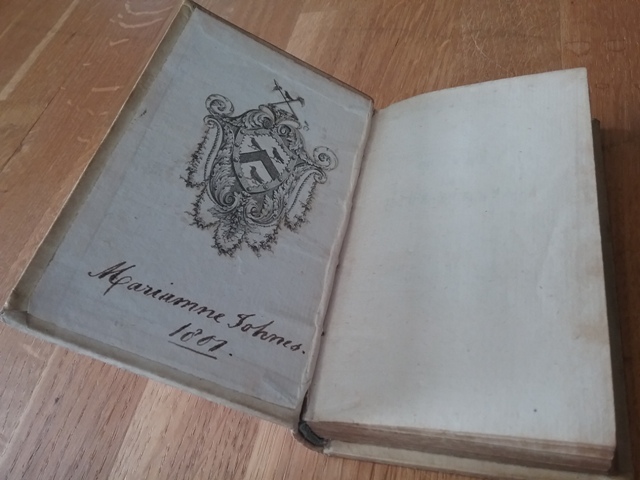

The ‘bookplate’ in Mariamne’s book

Tom writes:

One must not get too excited about small bits of paper……. but this is

potentially very interesting. I have seen another copy of this highly

decorative engraved coat of arms before, not stuck into a book and cut very

close around the engraved arms, so that it did not look like a bookplate.

And indeed the fact it does not have an engraved name under it begs the

question of what is it.

It has always struck Welsh bibliophiles as odd that Thomas Johnes never had

a bookplate for himself, even though his father, who was by no means so

famously studious, did. But this charming engraving in Mariamne’s book does

not look like a typical bookplate, certainly even less like a man’s one with

such a profusion of floral decoration, and of course with no owner’s name

engraved beneath.

So my first conclusion is that this is an engraving made after a drawing

sketched by Mariamne herself, very probably as a gift for her father. As

emphasised in “Peacocks in Paradise”, she was a brilliant botanist, and her

beautifully even copper-plate signature reveals a highly trained hand. It is

definitely not a bookplate made for Mariamne herself, since women did not

bear crests above their arms and as an unmarried daughter, her coat of arms

would have been shown within a lozenge (a diamond shape) not on a shield.

Bookplates were also engraved on small rectangles of copper only a little

larger than the engraved image, so that one can often see impressed in the

paper the edge of the copper plate, which I cannot see in your photo. So I

think that this engraving was engraved onto a larger copper sheet with this

copy of the resulting print cut down to fit inside this book.

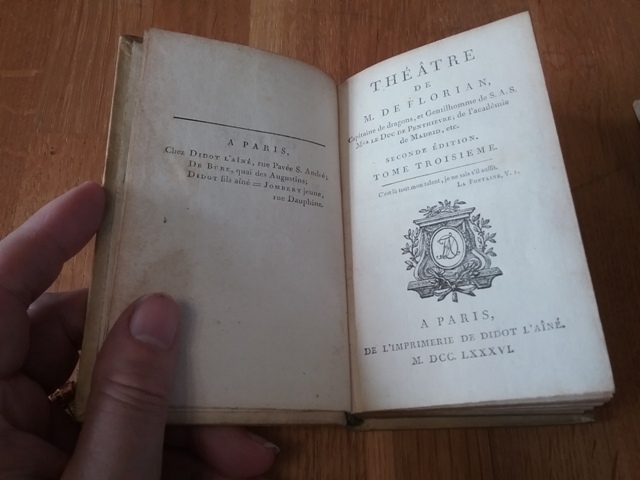

Being a remarkable and wonderful escapee from the great fire of 1807, we

cannot know what other helpful evidence has been lost, but this is the first

time I have ever seen this engraving stuck in a book, acting as a bookplate.

It is a most beautiful design and meticulously engraved (no doubt in London)

but its original intended purpose must remain unknown. It was not used in

anything published at the Hafod Press.

I have spent years looking for a book from Hafod (as opposed to printed there), but the nearest was to see one that had belonged to Thomas’s brother – expensive and of no interest.”

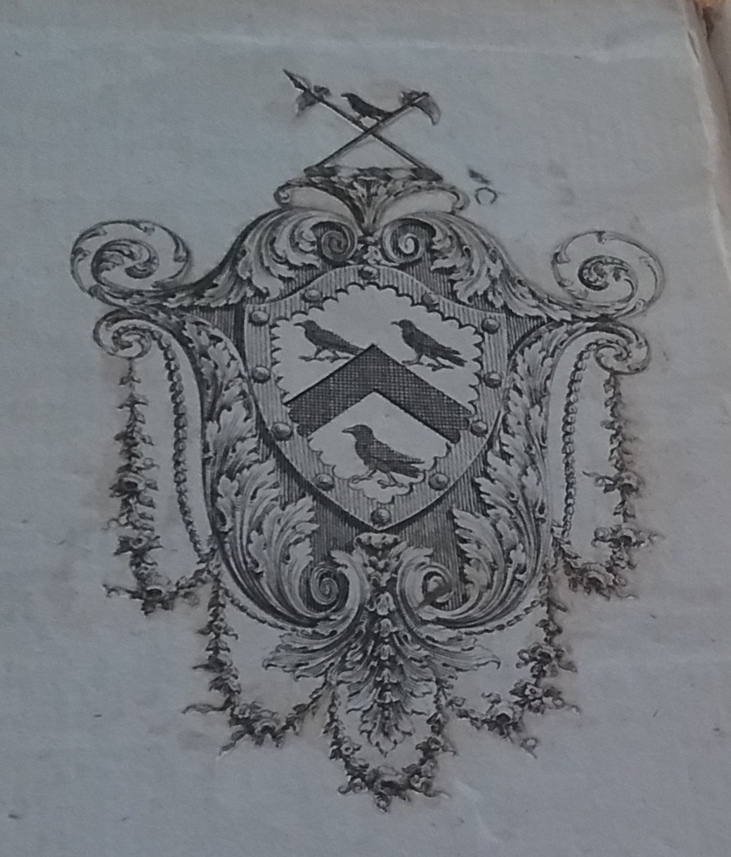

So what a coup for the Ceredigion County Archive and indeed the donor of this little book of forgettable plays! The arms are those of Thomas Johnes, but now we know that, being set in a shield rather than a lozenge, it is a masculine symbol, notwithstanding the abundant swags of flowers. The crest is also a masculine symbol, depicting crossed battleaxes in saltire proper, (a diagonal cross), but what is that cheeky chough doing standing on them?

The Johnes coat of arms, with embellishments, perhaps by a feminine hand?

Perhaps another book with this this device glued into it may one day come to light.