by The Curious Scribbler

I was one of thirty people who joined Beca Davies, Project Community Outreach Officer for the Pendinas Hillfort Archaeology Project, on a relaxed evening stroll around the lower slopes of Pendinas yesterday evening.

We met at the gate in Parc Dinas, traversed the middle path across the flank of the hill and returned on the lower path past the horse field and across the former rubbish dump. Stopping at intervals along the route Beca and Richard Suggett contributed their knowledge and further insights emerged from the group.

The Wellington monument, which stands within the iron age hill fort, was the brainchild of William Eardley Richardes of Bryneithin. Richard Suggett reminded us that public subscription had been limited and as a result the proposed equestrian statue of the Duke of Wellington was never placed on top of the gun barrel column. This is perhaps not surprising in view of the fact that it was not constructed until 1856, forty years after the battle of Waterloo! William E Richardes had, as a young officer, served in the army of occupation after the victory, but this was a monument stimulated by the death of the Duke of Wellington aged 83 in 1852. Possibly local interest in him had considerably waned by this time. More significantly the monument was sited such as to form a splendid eyecatcher when viewed from William’s home at Bryneithin! Today it would be considered very poor taste to erect a modern monument on top of such an important ancient site!

We looked out, across the Tanybwlch flats and its palimpsest of the trotting races etched on the grass, towards the tree-fringed hill top which is the site of the original Aberystwyth castle. This was Gilbert de Clare’s ring and bailey castle with a wooden stockade, built in about 1110 AD and repeatedly fought over by the Welsh and the Norman invaders. Llywelyn Fawr took it back in 1221 and later built a stronger fortification on the stony headland to the north. In 1277 after more than 150 years of skirmishing Edward I massive stone castle was built there, north of the mouth of the Rheidol but the name was never changed. Perhaps to the King and his strategists In London the geographic niceties of Aberrheidol Castle seemed unimportant. Prof Fred Long brought us a similar story from the 1940s. Two war time radar stations were to be built in Ceredigion, one at Llanrhystud and one at Tanybwlch. The Tanybwlch site was soon deemed unsuitable, probably because of the risk of flooding. So the radar station was installed on Constitution Hill instead, but was always known in the army documentation as Tanybwlch!

Our outward path then led us past the foundations of a two storey farmhouse which stood beside a natural spring adjoining the path. Beca showed us a black and white photograph where the farm was occupied and the farmer stands surrounded by chickens outside his front door. A barn stood at right angles to the house. The image is thought to have been made around 1930.

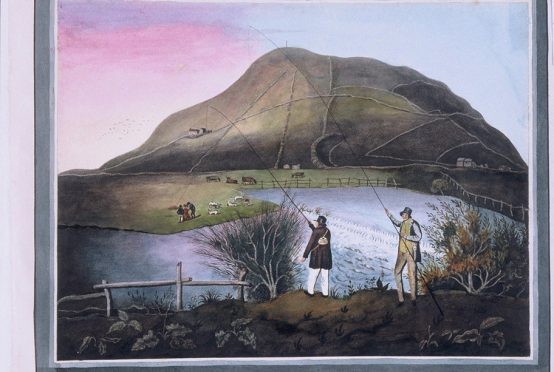

I’ve since looked out a much earlier picture, in the collections of the National Library of Wales. Drawing Volume 56 contains twenty two North Ceredigion scenes described as the work of ‘Welsh Primitive’ c.1830-1853 . Pendinas seems a little taller lumpier than it looks today and the foreground shows fishermen apparently below a weir on the river. But the divisions of the fields on the slope, the farmhouse, and the track we walked along seem accurately represented. The monument is depicted on the top, so the picture cannot be before 1856.

The primitive painter’s view of Pendinas ( NLW Vol 56)

The fishermen’s costumes may give further indication of the date.

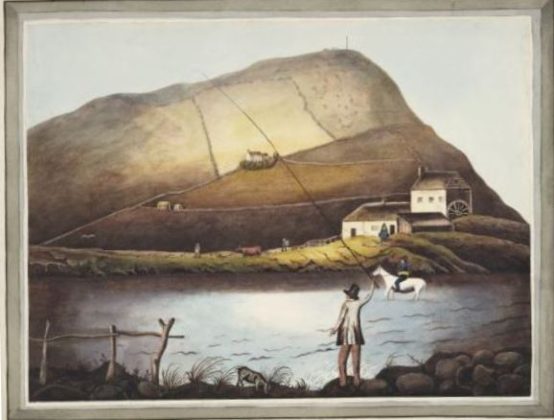

Another view entitled Pendinas and the River Ystwyth shows the farm on the hill and a rider fording the river near a watermill below the south slopes. Here too the monument is shown.

Pendinas and the river Ystwyth ( NLW Vol 56)

We learnt about the common lizards and slow worms which are numerous on the Pendinas. Chloe Griffith’s Nature of our Village project has led to a much wider understanding of the importance of the site. The spring is home to palmate newts. This water source was presumably also important to the iron age inhabitants, for without it they would have had to carry water all the way up from the river Ystwyth at sea level.

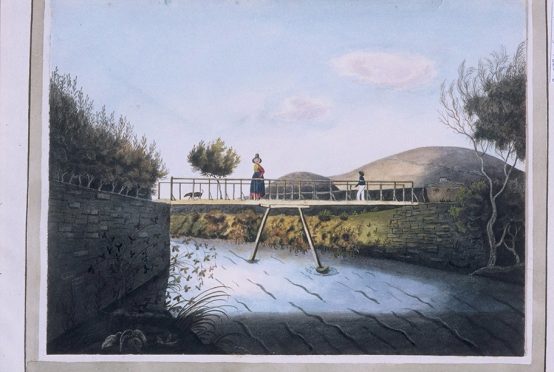

A third picture in the volume is captioned Tanycastell Bridge Perhaps it was painted a few years earlier, for the monument is not to be seen.

The bridge at Tanycastell ( NLW Vol 56)

One of the Welsh cobs at Spencer’s sheds entered into the spirit of the evening by trying to nibble Beca’s backpack. Frustrated in this endeavour it rhythmically and noisily kicked a big galvanised box until we all moved on.

The return journey was on a less historic path which was created after the old town rubbish dump had been covered with soil and re-vegetated in the 1990s. Willow scrub, gorse, brambles and nettles form an impenetrable undergrowth. Here the path cuts down through the reclaimed ground and fragments of bottles and polythene appear at the surface where they have been excavated by the rabbits, foxes and badgers whose paths run through the brambles and bushes.

In the 1980s I remember when the wire fences on the Tanybwlch flats were festooned with tattered polythene bags whipped away from the dump by the wind. We should be proud that Pendinas now looks almost as pristine as it did in these old paintings.

Pendinas in May 2020. The middle path traces the historic route across the flank of Pendinas