by The Curious Scribbler

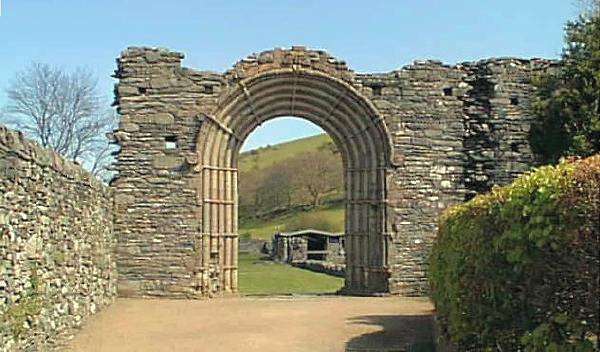

Strata Florida, at the end of the side road out of Pontrhydfendigaid is possibly one of the least-visited Cadw sites in Wales.

On a normal day, one or two visitors may be seen passing under the remaining arched romanesque west doorway of the Cistercian abbey church, and perhaps pausing to read the huge memorial slab reminding of us of the traditional belief that the 14th century poet Dafydd ap Gwilim was buried here under a great yew tree in the graveyard. Others come to the adjoining parish church in search of a more recent grave marking the burial in 1756 of a severed leg, and part of the thigh, of Henry Hughes, who was a cooper by trade. What accident with an axe, or perhaps a great metal hoop led to this misadventure? I have read that it was survivable and that the rest of this man was laid to rest in America. Come the resurrection he would have believed in, his leg and the rest of his body would presumably be reunited over the Atlantic.

This weekend though were two most extraordinary days, in which the field was thronged with vehicles, tents and a marquee, and bands of enthusiasts of all ages gathered in the church for lectures or for tours of the abbey site, the adjoining farm buildings and the wider landscape. Just an echo perhaps of the daily bustle of the 12th century when Strata Florida Abbey controlled vast tracts of land, productive of farm produce, timber and minerals. The event marked the launch of the Strata Florida Project, a concept which has been a twinkle in the eye of Professor David Austin for a couple of decades but now seems set to burst upon the world.

On Saturday morning he was surrounded by a densely packed throng of umbrellas as he explained the importance of the site. Size alone of the excavated ground plan shows that it had been a huge monastery, larger indeed than the famed Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire. Professor Austin explained the basis to believe that the abbey church was erected on a preexisting Christian site, and how the ambiguous structure in the centre of the nave floor, which is not quite correctly aligned with the axis of the church, is interpreted as a holy well incorporated, perhaps to honour older beliefs, when the Cistercians set up a new house in this part of Wales. The abbey enjoyed the patronage of the Welsh prince Lord Rhys of Deheubarth, and there are clues in the sources of the carved building stones, and in the celtic motifs on the west doorway that local Welsh tradition was not entirely subjugated by the incomers.

On Sunday a lecture by Prof Dafydd Johnston revealed a sense of the grandeur of these medieval buildings, and of the hospitality they offered. The peripatetic poets of the day wrote praise poems to their hosts, abbots and fine landed gentlemen, listing their assets, their buildings, farmlands, gardens, wives, offspring, fine food and general generosity. The picture emerges of soaring oak beams on stone arches, stained glass windows, a gleaming white tower, and lead so abundant it is described as encasing the church like armour. These poets were quite literally singing for their supper, and may have exaggerated, but they are a good historical source, perhaps far better than the more introspective utterances of poets today. In the early 15th century the abbey (which probably did supported Glyndwr’s rebellion) took severe punishment from the English army, who stabled their horses in the Abbey Church. Abbot Rhys ap Dafydd is praised for repairing the handsome refectory, and his successor Abbot Morgan for the beauty of the place.

We all know that Henry VIII brought the abbeys, quite literally, crashing down. The lucky recipients of this redistributed land and buildings were often given just a year to effectively destroy the monastic structures, perhaps adapting some parts of it for domestic use. Gentry houses thus emerged amongst the ruins. At Mottisfont Abbey in Hampshire which I visited last week, the nave became a long gallery, the core of a new gentry residence. Here the great church was largely demolished and cleared away, built into walls and vernacular buildings for miles around, while the refectory became the basis of the 18th century farmhouse Mynachlog Fawr ( or the Stedman House) as it appears in the Buck print of Strata Florida in 1742, and still stands today.

That farm has a story of its own, the last 150 years in the ownership of the Arch family of farmers. Charles Arch, a cherubic octogenarian known to millions as the announcer voice of the Royal Welsh Show treated a packed church to an elegaic description of his childhood growing up at the farm, and how as errand boy for his mother he would run the one and a half miles to the village, or be hauled from his bed at night by the local doctor to act as gate-opener for a house call to distant cottages up the gated road across their land. Most of the audience felt the tears well up as he described how as a young man he realised that the farm could not support three families and elected to seek his living elsewhere. ” The day I sold the pony, and did away with my dogs – was the saddest day of my life”. His brother’s family still farm the land, and since the 1970s have occupied a comfortable bungalow not far behind the old house. With extraordinary patience the Arch family have waited and waited for Strata Florida Project to gain momentum and purchase the old family home and its farm buildings.

Richard Suggett illustrated the importance of this fine old building, barely touched by electricity or indoor plumbing, and with many period features of the 1720s. There is a paneled parlour on one side of the front door and farm kitchen on the other, in which Charles recollects the bacon hanging from the ceiling and as many as 25 neighbours dining on Friday nights. The parlour still has its buffet cupboard next to the fireplace (an antecedent of the china display cabinet) an acanthus frieze painted on the ceiling above the coving, and a frightful didactic overmantle painting on wood above the fireplace. It depicts youth choosing between the paths of virtue and vice: the former rather staid and dull, the latter really nasty. Charles found it chilling as a child.

The Strata Florida Project aspires to restore and interpret all these layers of history and the wider landscape it inhabits. It reaches out to incorporate into the story every possible Welsh icon: The Nanteos cup: claimed to have arrived there via Strata Florida Abbey, the White Book of Rhydderch: possibly transcribed in the scriptorium of Strata Florida, poet Dafydd ap Gwilim: putatively educated by the monks of Strata Florida. This quiet backwater may soon become a hub of historical and modern Welsh culture.

Sunday closed with a procession from the parish church to the putative holy well in the abbey nave led by Father Brian O’Malley, a former Cistercian monk who had yesterday enlightened us with an account of the daily routine of Cistercian prayer.

Father Brian O’Malley leads the procession.

Photo copyright Tom Hutter

And displayed for the day in the adjoining ruined chantry chapel was the Nanteos Cup, on loan to its former home, courtesy of Mrs Mirylees the last inheritor of the Nanteos estate, who was also present with her daughter. For those with a spiritual bent it was an evocative day.

Prayers at the putative Holy Well

Copyright Tom Hutter

For the rest there was costumed historic re-enactment, archery, pole lathe wood-turning, refreshments, stalls and much besides.

Like this:

Like Loading...