by The Curious Scribbler

The other day I had the pleasure of handling two cannon balls, retrieved some thirty years ago from the archaeological excavations of Aberystwyth’s now rather fragmentary English castle. The castle occupies a splendid site on the headland south of the town, but is quite difficult for the unaided amateur to comprehend. Compared to magnificent structures like Harlech Castle and Caernarfon it is in a poor way. This I learned is largely due to its comprehensive demolition after the Parliamentarians had routed the Royalists in 1644. The walls were systematically destroyed by charges of gunpowder carefully placed, and large chunks of well-mortared masonry walls still lie well displaced from their original location, where they have been thrown by the force of the blast. From 1637 the castle had been the location of the royal mint, making coins with silver from the local mines. It also housed a great store of gunpowder for industrial use in the mines, and this is probably why the demolition, organised in 1649 by Lieutenant Colonel Dawkins and Captain Barbour, was exceedingly thorough!

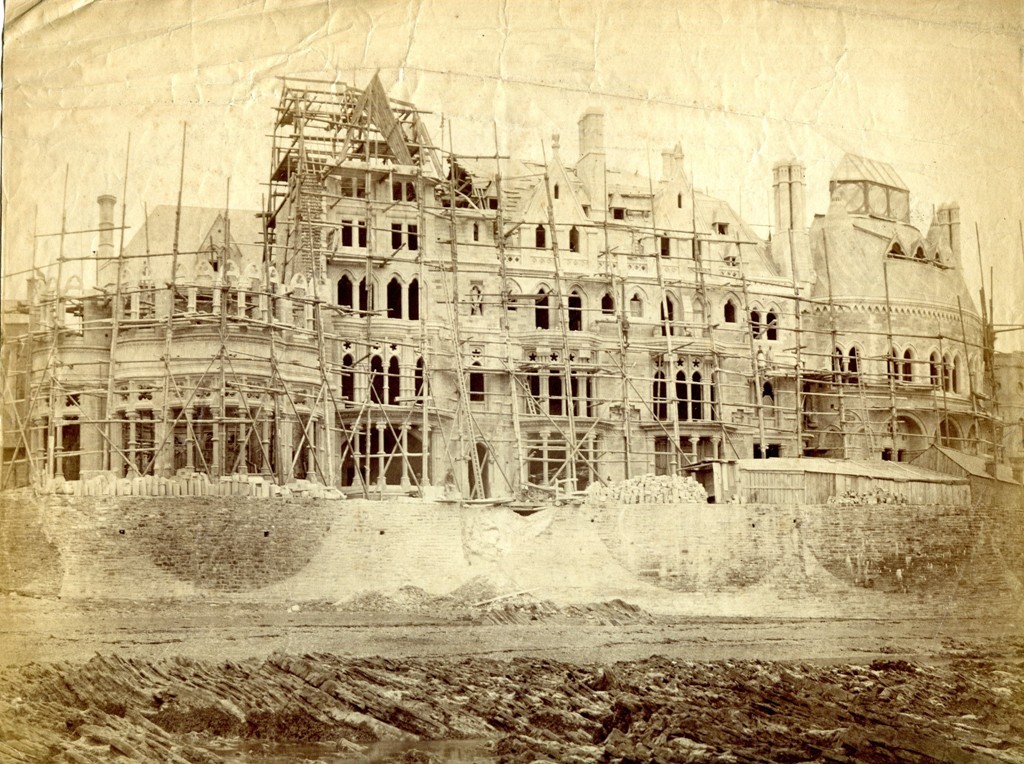

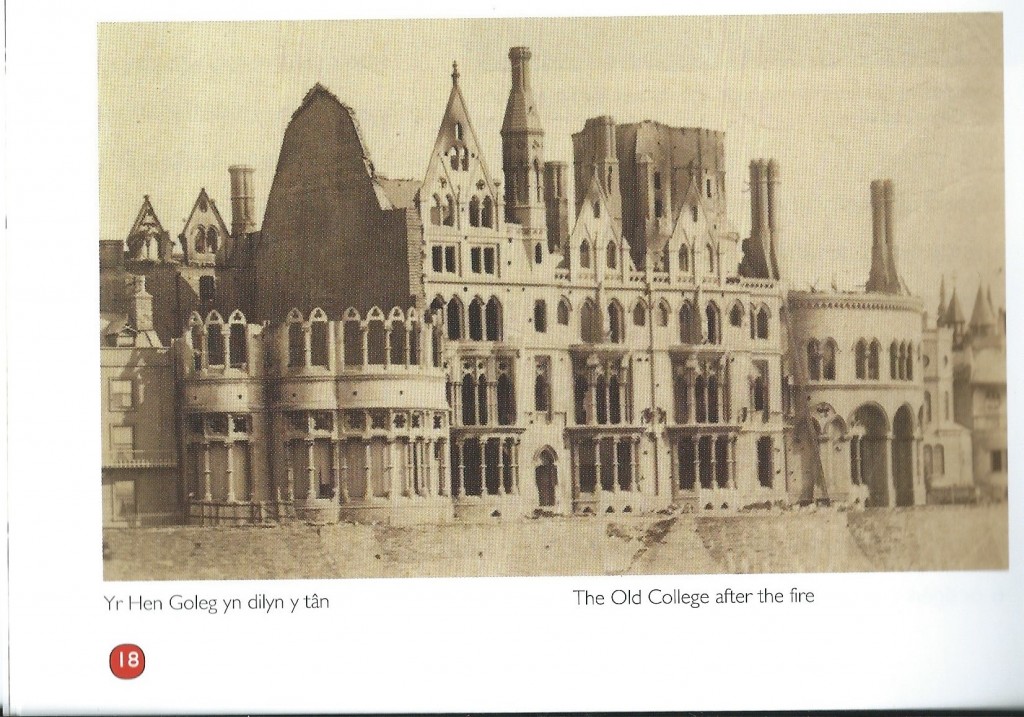

Huge chunks of the inner wall fell far from the wall line when the castle was demolished with gunpowder in 1649

The cannon balls are of stone, and were being examined for identification by a geologist. One is of limestone from Dundry near Bristol, and the other of a dense greeny-grey sandstone which could be from Somerset or South Wales. The surface is crudely tooled and pitted and to the casual glance they look strangely like a pair of seriously decayed Galia melons. They are heavy, 5½lb and 6½lb respectively, and just under 6 inches diameter. One has scarring on its side which could have been a result of its violent impact on the castle.

Two stone cannon balls which were among the finds excavated at Aberystwyth Castle under the direction of David Browne of the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historic Monuments Wales.

A search of images of similar cannon balls on the internet indicates that this is quite an ancient technology. Stone cannon balls such as these were in use as early as the 13th century, and are found in association with Muslim and Christian castles in Europe and Asia. (The Chinese had invented gunpowder in the 9th century and knowledge of gunpowder spread throughout the Old World as a result of the Mongol conquests of the 13th century. Cannon technology then became widespread). Stone cannon balls were employed in 1415 at Agincourt to deadly effect, they could bounce lethally through ranks of infantrymen. But the cannon could also explode killing the operators.

I found some marvellous contemporary illustrations on a forum www.vikingsword.com devoted to ethnographic arms and armour. They show how these imperfectly shaped cannonballs were fired from a cannon which was not cylindrical like the later models, but widening towards the mouth, such that the projectiles could be be imperfect spheres, and of somewhat varying sizes. Gunpowder was dropped in first, then packing material, and then the cannon ball, which was firmed into position with wedges of poplar wood, to create as tight a seal as possible. The seal could also be made with wet mud, but this needed to be allowed to dry before the cannon could be fired.

The contributor an enthusiast named ‘Matchlock’ is now deceased, so he will hopefully not mind me re-using his images. He also reproduces a detail from an Italian fresco of 1340, in which the loaded cannon is shortly to be ignited.

An American correspondent on the same thread,‘Kronkew’ added his own synopsis from an account of a siege at Soissons, which took place during Henry V’s campaign leading up to the battle of Agincourt in October 1415. The account shows that the English cannon was clearly a dangerous weapon to operate.

| The French were besieging Soissons, an English defended city nominally under the rule of a French faction, the Burgundians, that sided with the English, defended by some English archers, and some mercenary gunners. it described them placing a gun in a tower overlooking the French camp.

Meanwhile the French were getting off a rapid fire from their siege cannon, a whopping three rounds per day, they had to wait for the wet clay and straw mix wadding to dry before they could fire. Anyhow, the English cannon, described as made from forged and welded bars of iron re-enforced by hoops of iron, was apparently in a fairly rusted and pitted condition, having been stored in the basement without much care. It was ‘twice as long as a bow-stave’ and ‘hooped like an ale pot’, resting on a wooden carriage. They mentioned it was tapered (much like the illustration) because the stone balls were of inconsistent diameter, the taper allowing the ball to get to a place where it fits, assisted by the wadding of soft loam. The gunners loaded the wadding, they waited the requisite time for the wadding to dry out before the stone ball was inserted, and wedged it in place with small wooden wedges to keep the stone ball from falling out if the rear was elevated & to ensure it was held tight against the wadding and powder charge. The cannon was considered a demon due to its sulphurous breath on firing, so a priest was brought up to it to bless it with holy water and, to ensure no devilry ensued, he stayed. The senior gunner then primed the cannon with a stripped goose quill filled with powder, fired the cannon with a long taper, it promptly blew up, killing the crew and the priest. The city fell when one of the English lords sold out to the French and opened the gates. The Aberystwyth cannonballs may be assumed to be of a very similar date. CJ Spurgeon in his article Aberystwyth Castle and Borough to 1649, records the varied fortunes of the castle which withstood assaults from the Welsh in 1287 and 1295. In 1404 after a prolonged siege Owen Glyndwr took the castle and there signed his famous treaty with Charles VI of France. The following year Prince Henry ( later Henry V) is recorded to have brought cannon from Bristol and, in ( according to Spurgeon) one of the earliest records of their use, he recaptured the castle in 1408. It is particularly satisfactory that the limestone cannon ball can be identified to come from Dundry, near Bristol, where the stone for many medieval buildings was also sourced. It was probably carved locally and brought to Aberystwyth along with Henry’s cannons. |

![By Chris Sampson (http://www.flickr.com/photos/lodekka/5646346212/) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.letterfromaberystwyth.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Tropicana_frontage-1024x682.jpg)