by The Curious Scribbler

I had an enjoyable day at the Morlan Centre in Aberystwyth on Saturday, at the Archaeology Day organized by the Dyfed Archaeological Trust. The remit of archaeologists today stretches from the very ancient to the extremely recent, and this was reflected in the range of talks. The morning started with the archaeology of yesterday while by the afternoon we were taken back three thousand years to the beginning of the first millienium BC.

Alice Pyper had been having fun exploring the archaeology of Llyn y Fan Fach, the glacial lake which now supplies Llanelli with a clean water supply. It was not always thus: the water system was built by conscientious objectors during the first world war. Some thirty of them were compelled to live in two drafty huts at 1200 feet above sea level to work on the project. Field archaeology involved excavating and recording the footings of these huts. Documentary sources including newspapers and humorous sketches by the objectors fleshed out the story. This workforce was of Englishmen who had already served time in prison for refusing to fight. Michael Freeman pointed out that in Wales objectors were less harshly treated, and that most of the thirty conscientious objectors in Ceredigion were not imprisoned and were allowed to keep their jobs.

Also representing the very recent past is the built heritage of the 20th century. Susan Fielding of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales treated us to photographs of a splendid succession of architectural gems or carbuncles, some listed, others already demolished. The architects of the Percy Thomas Partnership ( familiar to us here for much of the Penglais Campus) kept cropping up, with Harlech College, Trinity Chapel at Sketty, and the soon-to-be-demolished Broadcasting House at Llandaff, all redolent of the 1960s. The Prestatyn Holiday Camp ( 1935) and the Rhyl Sun Centre (1980) have both gone, both extravagant expressions of their times, and dear to many people’s holiday reminiscences.

Rhyl Sun Centre by Gillinson Barnett & Partners

Source:Architectural Press/Archive RIBA Collections

The Shire Hall in Mold, dubbed Britain’s leading ugliest building, and the Wrexham Police station are brutalist buildings which will perhaps not be mourned too much. Still standing, and crying out for a role in a brooding TV Drama is Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones at Amlwch – one of the very first 1950s comprehensive schools.

Less is sometimes more, and it was strangely gratifying to learn from Clwyd-Powys Archaeologist Paul Belford that we really don’t know whether Offa’s Dyke has a great deal to do with King Offa, when it was built, or quite what it was for! Opportunities to excavate this world heritage site are few and far between, but one did arise from the actions of a Chirk man who bulldozed 50 yards of it in order to build a stable. ( His ignorance of its historic significance saved him from prosecution in 2014). Perhaps this vibe for vandalism is in the air around Chirk. Paul showed us a lidar image of the grounds of Chirk castle. In the 17th century Landscape Architect William Emes flattened much more than 50 yards of it to create smooth parkland, and submerged a further length of it in an ornamental lake!

Low water levels in 2018 revealed Offa’s Dyke in the lake at Chirk Castle. Picture: The Shropshire Star

Two afternoon sessions concerned the days of the iron age hillfort, a period lasting from at least 1000 years BC. Hillforts are scattered like measles across the whole of the map of Wales, and with techniques of aerial photography and lidar more are still being discovered. Either they are on hilltops with ridge fortifications all the way round, or they are promontory hill forts, situated on the edge of a cliff or at the confluence between two valleys such that fortifications are not needed at the steeper sides. The archaeologists have been seeking evidence both within the enclosures, where groups of round houses were situated, and outside them where burials, and farming actvities took place. Ken Murphy rounded off the day with an account of the iron age chariot burial discovered last autumn in a field not far from a hillfort at an undisclosed location in west Pembrokeshire. Being buried along with your two wheeled chariot and your horse requires a pretty extensive hole and this type of burial is well known from East Yorkshire. The chariot burial discovered at the evocatively named village of Wetwang, revealed the human skeleton curled up between the wheels of his chariot, and the horse laid transversely at his head. The limey soil chemistry in east Yorkshire does not dissolve the bones.

In the Welsh burial bronze fragments of the bit, bridle and horse ornaments testifies to the horse, and an iron sword to the warrior, but their bones are long dissolved. The iron rims of the wheels and the imprint of the wooden chariot were found. These items are undergoing conservation at the National Museum of Wales and will then be put on display.

Photo credit: Archaeologists exposing the wheels of the Pembrokeshire chariot.

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Embarrassing is indeed a good word for what has been done to the campus in the last two years!

Embarrassing is indeed a good word for what has been done to the campus in the last two years!

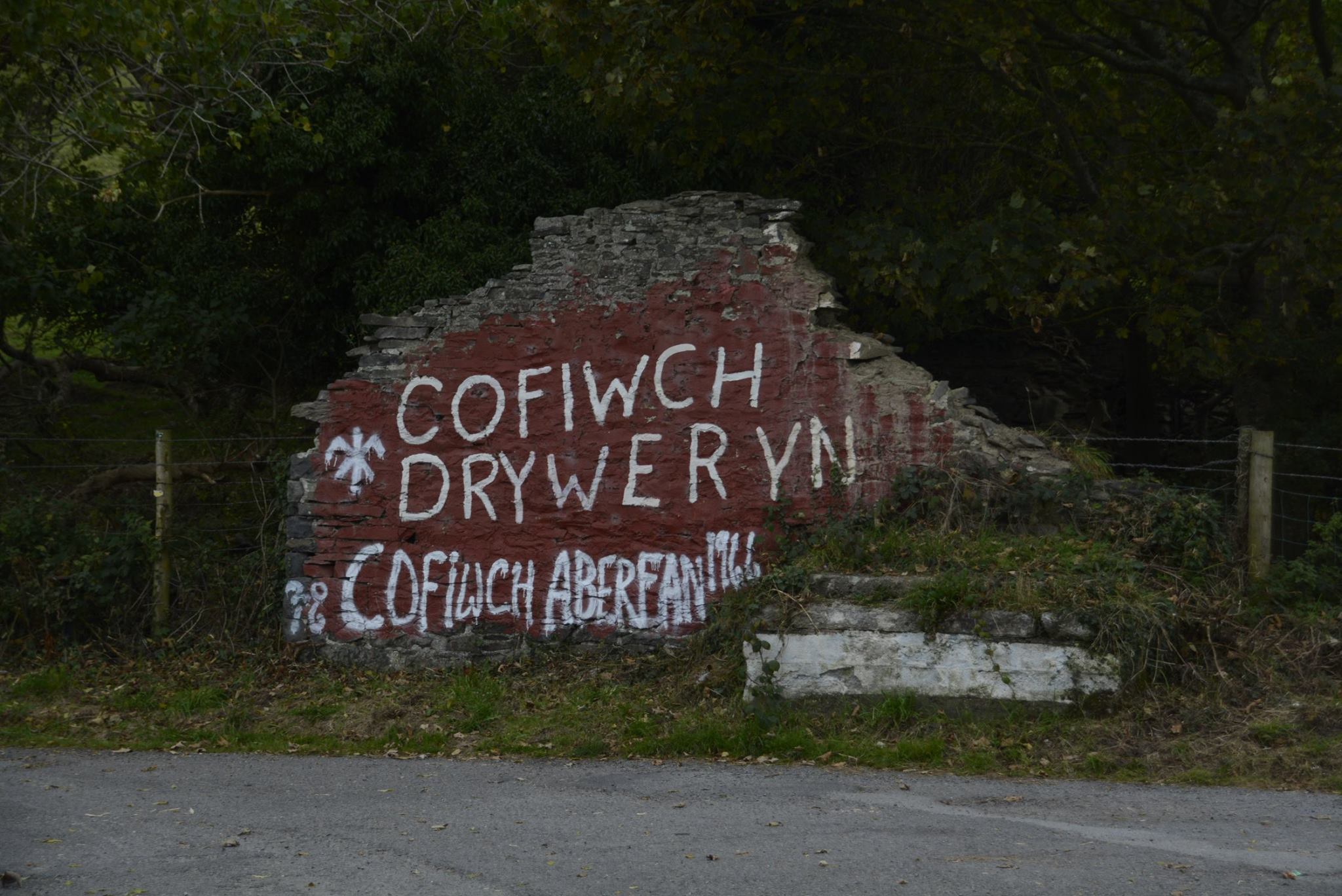

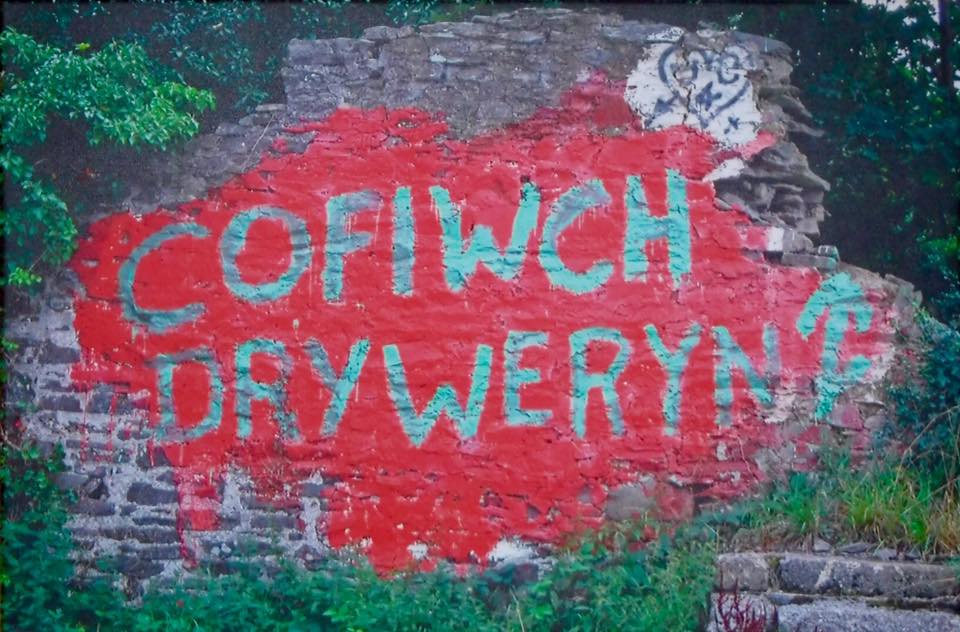

Last weekend’s morph was perhaps the least creative. The new daub seems superfluous – we already have the well known Elvis rock at Eisteddfa Gurig. A second ‘Elvis’ lacks the historical relevance of the first, which was a corruption of the electioneering notice for Councillor Elis. One wonders exactly what the author of thinking of.

Last weekend’s morph was perhaps the least creative. The new daub seems superfluous – we already have the well known Elvis rock at Eisteddfa Gurig. A second ‘Elvis’ lacks the historical relevance of the first, which was a corruption of the electioneering notice for Councillor Elis. One wonders exactly what the author of thinking of.