by The Curious Scribbler

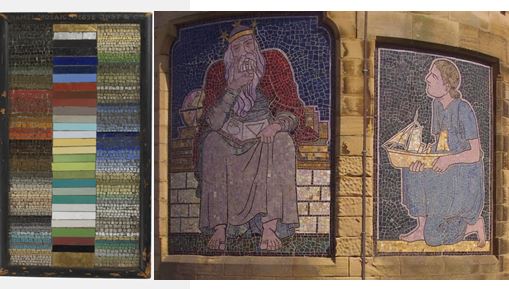

Few of the throngs of elderly dog owners in the cafes of Barmouth take time out to examine the Millennium sculpture on the quay, and those who do may merely observe that it is a work by local sculptor Frank Cocksey, entitled The Last Haul. It shows three human figures, in different period costumes, together pulling together on a thick rope. They lie backwards like the contestants in a tug of war, and while they are obviously freshly carved in white marble, the un-carved plinth below looks grey and pitted and could be mistaken for some kind of concrete.

Barmouth Millennium sculpture – The Last Haul by Frank Cocksey

In fact the entire block is of white Carrara marble from Italy, the material so beloved of Michelangelo and figurative sculptors ever since. For around 300 years it lay on the seabed some 30 feet down and a few miles off the beautiful shore between Barmouth and Harlech. It was one of 42 blocks found on the sea bed, neatly shaped and ranging in size from 13 inch cubes to great blocks like this one, 9ft x 3ft x 2.5ft in dimensions. All were extensively bored by marine creatures.

The wreck was first discovered in 1978 and excavated by the Cae Nest group of archaeological scuba divers. Nothing of the wooden ship remained, but the cargo lies as it was loaded amidships, and other finds include 25 cast iron cannons, a bronze bell dated 1677 and coins from 10 countries among which french coins predominate. They also found navigational dividers, pewter plate and fine cutlery, a dental plate, a seal, remains of pistols and a rapier. Opinion is divided as to the nationality of the vessel. The Barmouth plaque states it was a 700 ton Genoese galleon, the Coflein entry suggests, on the basis of the coins, and the French pewter, that it may have been a French trader. What is of little doubt is that it was a well-armed vessel, carrying a valuable cargo, and that it went down after 1702 ( the youngest coin) and probably around 1709.

Who in North Wales had sent for such a cargo? The graveyard at Llanaber Church might provide a clue, for it is surprisingly rich in white marble memorials dating as far back as the mid 18th century, though I haven’t noticed any as old as the presumed wreck. Could these pieces have been destined for an enterprising monumental mason?

The graveyard at Llanaber Church is rich in 18th and 19th century gravestones of white marble

There is a popular alternative theory: that this was a ship blown off course, missing the English Channel and forced up past Cornwall into the Irish sea where it eventually foundered. The first decade of the 18th century saw Sir Christopher Wren rebuilding St Paul’s cathedral, a project requiring a great deal of Carrara marble.

Marble is a limestone, easily excavated by the sea creatures which secrete acid to dissolve their homes as the blocks lay under the sea. The large round-ended holes were made by molluscs, the smaller interlaced hollows are the homes of sponges, while polychaete worms bored several centimetres into the rock. As Frank Cocksey carved away the eroded blocks he has exposed fresh white marble. In places the worms have penetrated even deeper than his carving, as is shown on the leg of the youngest seaman.

Bivalve, sponge and worm borings in the end of the large block of Carrara marble bear witness to its 300 years under the sea.

Marine worm borings puncture the 21st century sculpture ” The Last Haul” by Frank Cocksey

It has been suggested there was at least one survivor from the wreck, Juan Benedictus whose death is recorded in the Llanendwyn Parish Register in 1730, and tradition has it that timbers and artifacts from the wreck found their way to Corsygeddol Hall. Seafaring in the 18th century was a risky business and many ships must have foundered on this coast. We will never know exactly what happened.