by The Curious Scribbler

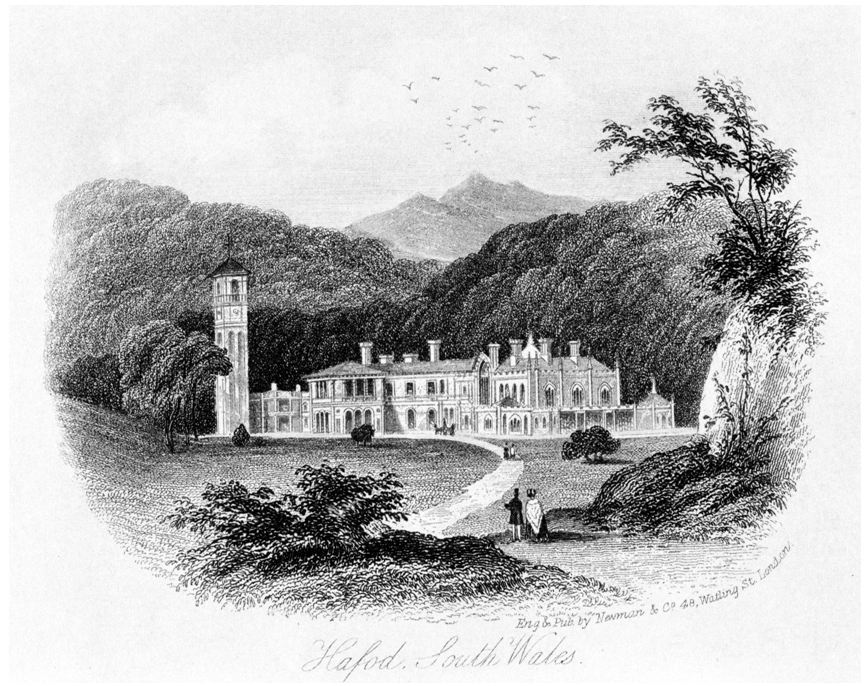

My first home in Wales, thirty years ago, was in Castle Hill, Llanilar, a trim Georgian mansion built in 1777 by John Williams. It is today still occupied by the Loxdale family: direct descendants of the brother of Shrewsbury heiress Sarah Elisabeth Loxdale, who married John Nathaniel Williams, the son.

In the mid 1980s we occupied the top flat, which comprised the entire third-floor of the old Georgian house, in which a central staircase opened onto a large landing giving onto four equally huge rooms. An ambitious adaptation in the 1960s had added an external wing containing only a staircase, which gave separate access to our floor. Once upstairs we enjoyed a giant sitting room and an equal sized bedroom overlooking the garden, while the other two rooms had been divided to create dining and kitchen in one and a second bedroom plus access corridor in the other. I have always remembered the original latch fittings on the four doors onto the landing. Each was designed to allow a guest to unlock their door to the servant on the landing, without the inconvenience of getting out of bed. The furniture was antique and the whole ambiance would now be called shabby chic. The old oak floors undulated underfoot, and at night, mice could be heard scrunching behind the skirting boards. The only serious disadvantage was for my tall husband, because the four original doorways were lower than 6 feet whereas the newly formed doors were standard sized. It was a slow learning curve to duck between the hall and the sitting room while progressing normally from sitting room to dining room and kitchen.

We lived here when our first daughter was born and for almost 3 years afterwards. Often on fine days, with my baby in a carrier, I would stroll up the hill past the farm, climb a gate and head off up to the hill top from which Castle Hill takes its name. Truly it was the top of the world up there, views spreading panoramically in every direction so that even the distant mountains appeared on the level with my vantage point. The ground was grazed by a young cattle and sheep, tussocky with with patches of gorse and bracken and the silence (except when shattered by low-flying jet) was immense. I never met anyone else up there (there is no public right-of-way) yet it never felt lonely – a place with great resonance of the past.

Recently I revisited Castle Hill with the Ceredigion Historical Society under the expert leadership of Toby Driver from the Royal Commission for Ancient and Historic Monuments. As we stood once again on this hilltop earthwork, Toby took us through the history of the fertile Ystwyth valley. The Welsh landscape is so easily dismissed as empty. Instead it is better imagined teeming with life and human activity ever since Neolithic times. Pollen sampling has revealed that the wildwood is long gone, active deforestation was well underway by the late Iron Age and by the early Roman period the woodland cover was probably similar to that we see today.

Other recent archaeological advances include the discovery a few years ago of the substantial Roman villa between Abermagwr and Trawscoed, which is a few miles up the Ystwyth Valley. The Romans had a camp at Trawscoed, but they did not merely march through Wales subjugating the Celts. They settled and farmed here bringing costly artefacts such as glass and pottery from other parts of their Empire.

Toby explained the many phases of occupation of the Pen y Castell hillfort. Earliest is a curving earthwork revealed by aerial laser scanning, which probably represents a Bronze Age hillfort. This was superseded around 400 BC by a substantial ( 1.7 hectare) Iron Age hill fort with a gateway approach on the south eastern side. Its ramparts surmounted by a timber palisade it would have been an intimidating structure to approach from below. Protecting a village of round huts and grain stores, this would have been just one among the many fortified hilltops marking the Iron Age communities of the region. A larger community has left its distinctive footprint on Pendinas, where the Ystwyth reaches the sea.

We gathered within the ramparts on the southern side of the Pen y Castell summit.

Puzzlingly, the other half of the overall summit is inaccessible due to a deep cut trench or cutting running east-west. Scholars have puzzled over this feature throughout the 20th century. Some believe that a medieval motte and bailey was superimposed on the site around 1242. If so it was a Welsh one, unlike the Norman castle first built at Tanycastell, Rhydyfelin which gave its name to Abersywtwyth. The northern part may then have been the location of the keep, approached by a bridge across the chasm. Others suggest the trench was a created by post medieval quarrying to supply local building needs.

Much more archaeology is needed to tease out the history. The most recent finding here has been traces of a trapeziodal enclosure on the slope below the fort which is interpreted as another Romano-British farmstead, perhaps a tenant of the Roman villa at Aberamagwr.

Gathered in the sunshine with bluebells at our feet we all enjoyed that very special sense of place, and the realisation that this is not ‘Wild Wales’, but instead extremely tame Wales, a scene of homes and villages supported by pastoral and arable activity for more than 5000 years. The parade of wind turbines on the skyline is perhaps deplorable, but can also be seen as just another symptom of fifty centuries of human exploitation of the landscape.

Viewed from the beach, it became clear that the sea had excavated a cave into the void beneath the shelter. A group of police assembled as the tide receded, to prevent risky exploration beneath the hole in the roof. I am told this promentory was once the site of tha Aberystwyth gallows. Another bystander said there had formerly been changing rooms accessible from the sands below the shelter.

Viewed from the beach, it became clear that the sea had excavated a cave into the void beneath the shelter. A group of police assembled as the tide receded, to prevent risky exploration beneath the hole in the roof. I am told this promentory was once the site of tha Aberystwyth gallows. Another bystander said there had formerly been changing rooms accessible from the sands below the shelter.