by The Curious Scribbler

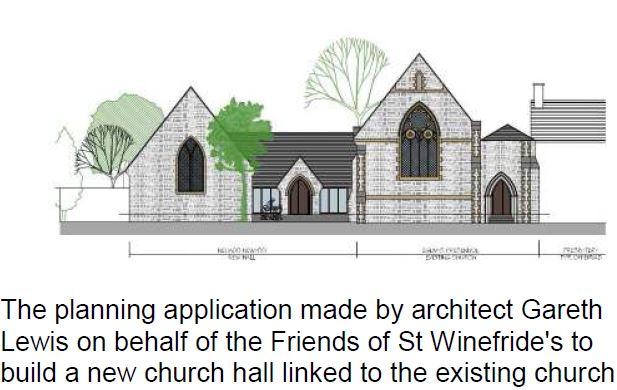

Before the show opens, stewards calculate the number of points scored by winning contestants at the Llanfarian Show

This is a part of the world where, bucking the trend, the Village Horticultural Show is alive and well, as it has been for most of the last century. It is an extraordinary co-operative effort which unites communities. Everyone has a vital part to play: Committee, competitors, judges, spectators. For just two hours or so a thousand or more exhibits are collected under a marquee or village hall roof, and then, tea taken, the prizes distributed, and old friendships renewed, the whole is dispersed once again leaving no imprint other than the carefully assembled list of winners in the following week’s paper.

I judged the Flowers at Llanfarian Show last Saturday.

It is a heavy responsibility. For me the morning began at 11-30am when I presented myself at the primary school to join eleven other specialist judges, many accompanied by their husbands or wives. We sat on the miniature pupils’ chairs and consumed ham salad with hard boiled egg, coleslaw, beetroot and pickles and thiny sliced brown bread, trifle and strong tea. Conversation was sporadic and a little tense. Judges are mainly recruited from a little farther away, so they know each other less well than the Stewards, all locals who, having presided over the staging of the competitors’ entries, congregate on a separate table for their meal at noon. Judges are also tense at their impending responsibility, some are faced with ranking the merits of widely diverse objects, ( Any item in Applique, An Item of Pottery) others with judging the quality of a slew of extremely similar cakes, jams or flowers. Entries must be rigorously as per schedule – woe betide the judge who fails to notice that an extra bloom found its way into the class for six sweet peas, or who allows a Decorative dahlia to insinuate itself amongst the entries in the Waterlily dahlia class!

The Floral Art judge has perhaps most to fear. Tradition demands that she produce a written critique of each exhibit, which is propped up for all the public to read during the afternoon. These critiques are traditionally encouraging in tone, but nonetheless must expose weaknesses in order that basis for winning entries is generally understood. And the first prize may not go to the arrangement most pleasing to the untutored eye, but to the one most interpretative of the arrangement’s set title. Little wonder that we judges scurry home before the competitors stream in at 2-30pm.

Many locals enter just a few classes with their home grown produce, for the fun of the chance of a prize, but there are also the titans of the show bench who compete at a local show almost every weekend of the summer season, and whose targets are the cups. Special Cups for most points in a class may be won outright through three consecutive wins ( or five spread over time). The big names in local showing have display shelves at home crammed with trophies, some on one year placement, many others won outright, their gleaming sides inscribed with the names of the annual winners of their past. Other cups are Perpetual Cups, returned every season to their awarding show.

One such competitor is Buddug Evans, whose carefully managed garden yields roses, gladioli, geraniums, african marigolds, spray chrysanthemums, petunias, pansies, sweet peas, asters, dahlias and potted plants just as the show schedule demands. It is among the dahlias that competition is particularly hot. Half the length of the hall is devoted to competition in seven distinct subgroups of dahlias, glorious matched trios of strong straight blooms staged in the tall green metal vases which professionals favour. There were up to eight good entries in each of the dahlia classes, so she did not go unchallenged by other skilled growers. Beating Buddug in any contested category has become a target in itself. For total points she was the clear winner.

At the end of awarding thirty Firsts, Seconds and Thirds in 30 Classes it fell to me to select the Best Exhibit from among the Firsts. Often this falls to trio of dahlias or to a gigantic single chrysantheum bloom the size of a newborn baby’s head. But this year, among the entries in Class 60, ‘Vase of Garden Flowers from Own Garden’ nestled an outstanding fanned display of huge creamy gladiolus spikes, the smaller gladiolus ‘Dancing Queen’ with red blotched throats, creamy decorative dahlias, pure white ball dahlias, spray chrysanthemums and huge white snapdragons. Judging is done while the competitors’ cards are concealed, so it was the final revelation to turn over the label and find this blaze of perfection, and worthy winner of the Best Exhibit Perpetual Cup was the work of another veteran competitor Gwyn Williams.

I left as Councillor Rowland Jones of Llanilar arrived to open the Show, and the public, including Ceredigion MP Mark Williams and his family arrived to scrutinise the tables. I passed the winning exhibit in Class 126 Best Misshapen Vegetable where it lay outside the tent. If winner, farmer Ieuan Jones plans a long flight or coach journey, it seems he has grown the ideal marrow!