by the Curious Scribbler,

The second great loss to campus biodiversity last autumn was the grubbing out of a long shrub border which ran from Student Welcome Centre to the Llandinam building. Three trees: two Phillyreas and a Griselinia were spared,but the rest of the hydrangeas, olearias, escallonias and fuchsias were scraped away leaving the sea of mud. The scene was recorded in November see http://www.letterfromaberystwyth.co.uk/penglais-campus-the-destruction-continues/

The justification allegedly was Health and Safety – the installation of railings at the top of the drop at the back of the border, a drop which at the Llandinam end was a mere 18 inches, but at the the other end about twelve feet.

New turf replaces the mixed borders on Aberystwyth Campus

Last week I revisited to see the completed works. The border has now been replaced by a stunningly green sward of new turf. This green desert monoculture looks a bit unexpected doesn’t it? Gardeners know that this bright green turf will soon lose its lustre in the shade of evergreen trees. Ecologists know that while a species-diverse grassy meadow is an asset, new uniform turf is little more desirable than astroturf. The tragedy is that this expensive form of re-instatement is only the briefest of fixes, a decision which would only have been taken (and was) by Estates Department staff totally unqualified and unversed in horticulture. The fear is that, chagrined at the consequences, those same decision-makers will then cut down the remaining trees to save the new grass!

A student petition was sent to the Estates Department in November. In part the letter read

“large patches of green space and hedges have been cleared and replaced with either woodchip or grass…. this poses large uncertainties with regard to the future of biodiversity on campus and our cherished EcoCampus Gold Award. .. As students we are very proud of our campus and want to work with the University to make it an even greener space…”

I don’t believe this was the kind of greening that they had in mind.

As for their health and safety, the new railings are just two horizontal rails, of the sort that many a drunk student has vaulted over for fun. Where the drop was protected by a hedge of shrubs it was far less accessible. The foreground view through to the IBERS building is now just a mish-mash of different generations of fence, and a paved path to nowhere.

Looking through to the IBERS green roof, we now see a forest of railings and a path going nowhere

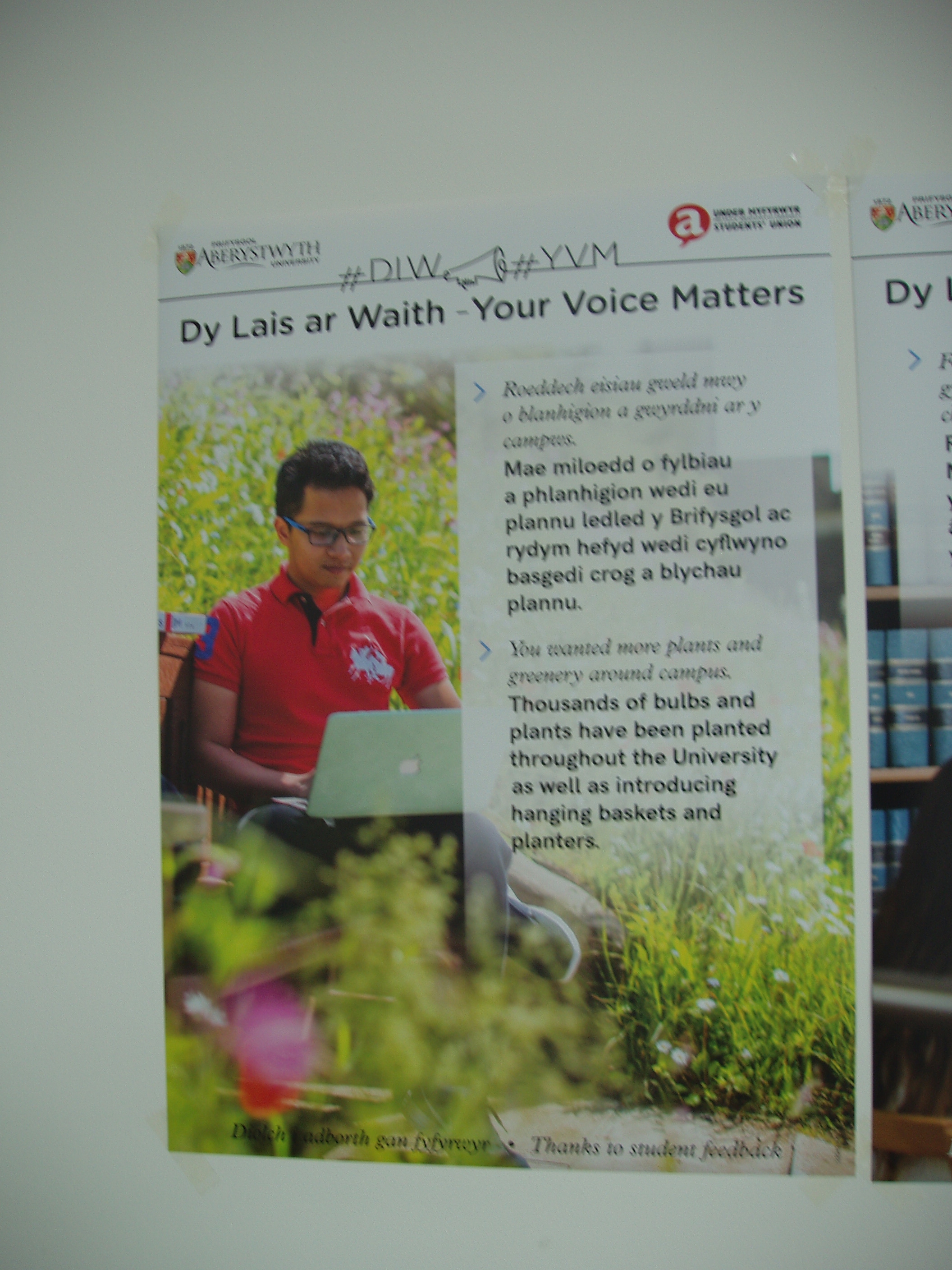

At the same time a new self-congratulatory PR poster aimed at students has appeared in University buildings.

The students may have asked ‘more plants’ but they are not getting them – unless we count the individual seedlings of grass! They aren’t getting ‘more greenery’ either.

Did the students specifically ask for hanging baskets? ( the ones who signed the petition I saw certainly did not). And did they ask for them to be spread randomly around the grounds? Playing spot-the-hanging-bracket might become a new student activity. A lone bracket has been affixed to the elegant timber facade of the IBERS building. Another sticks out adjoining the steps to the Arts Centre and Students Union. Yet another is screwed high on the wall at the entrance to Geography and Earth Sciences.

An odd location for a lone hanging basket

While a hanging basket gives a quick fix to a suburban patio a large landscape need a far more considered approach and on a practical level, watering these floral displays is going to be quite a challenge. We have seen other phases of expensive and impractical gimmickry come and go. The IBERS green wall, for example, has been quite rightly cleared away, for it soon looked like an abandoned garden-centre sales area on end!

The new IBERS building on the campus sported, until 2017 a most deplorable ‘green wall’

One of the current public enthusiasms, quite rightly, is Bee Friendly Landscapes, I believe that Aber students have already formed a bee-friendly group. Woodchip, monocultures of turf and the occasional hanging basket are not bee-friendly. That extensive bank of flowering cotoneasters below the Hugh Owen Building most certainly was!

There is no landscape expertise guiding the recent changes on campus. Buildings Maintenance, Health and Safety, Disability Access, Controlled Parking and other pressures all chip away at the carefully designed plantings which earned Aberystwyth University its Cadw Grade II* listing. Soon there may be very little left to justify that accolade.