by The Curious Scribbler

Long before the days of instant messaging the Victorian family might keep its dispersed members entertained by producing a journal to which its members contributed choice memories, sketches, verse, and family news. One such family were the Palmers, a tribe of 19th Century printers, teachers and clergymen one of whom, George Josiah Palmer is remembered as the Founder of the Church Times. At the beginning of the 20th century the Palmer family journal “The Pilgrim” was laboriously typed, bound and circulated by post around ten or more family members. It appeared intermittently between 1901 and 1907.

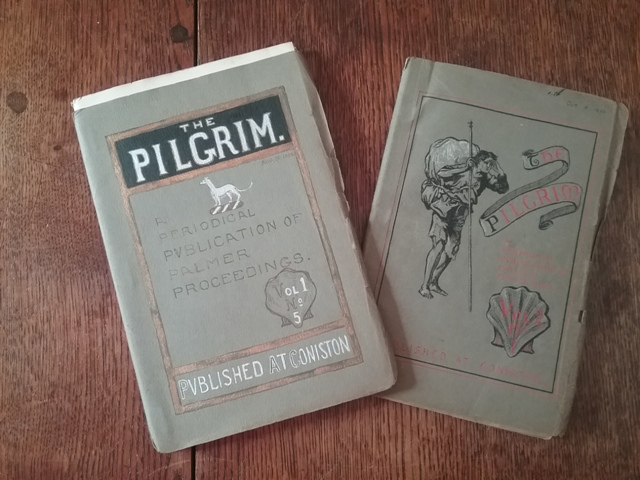

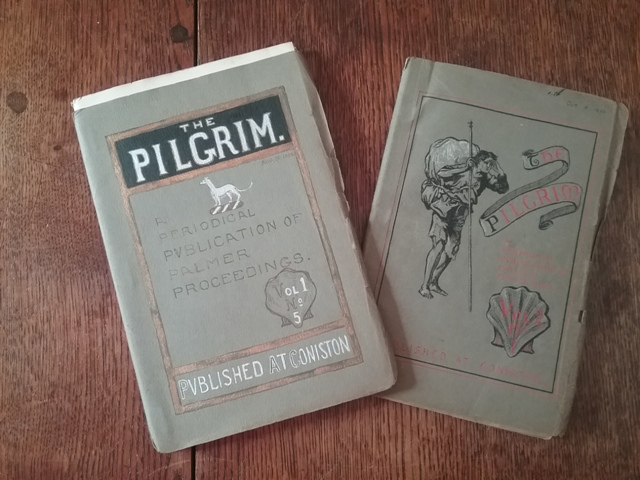

‘The Pilgrim’ a family journal produced by the Palmer family in 1901-1907

A stirring reminiscence was provided by Carey Linnell Palmer, and published in two installments in Volume 1 No 5 and Volume 2 No 1. It must be acknowledged that the account of the two young men’s adventures at Crystal Palace (George aged 26 and Carey aged 17) may have been embroidered a little in hindsight, for the story reproduced here was written by Carey Linnell Palmer in 1902, thirty years after the alleged events. However since the target audience included family members who had been present in the Palmer home at 6 Percy Circus, Clerkenwell on the fateful day in 1872, I incline to the view that it is probably not entirely a work of fiction. I reproduce it here for the edification of today’s balloonists.

AFTER MANY DAYS

It was a steaming hot day in the August if 1872 and a holiday. The house at Percy Circus as was its wont, looking uninviting, and the back garden didn’t offer much in the way of a jaunt. George, who was always keen on engines and trains, voted we should spend our pocket money going up and down the underground. “Well”, said I, “that’s pretty good fun, but I think it’s possible to go one better. How about the Captive Balloon at the Palace? It’s only a bob a head, & a jolly tough rope, and heaps of other things to see besides.” Dear George didn’t often use slang, but this time he said he was ‘All there’, and with the help of the train we soon arrived at Sydenham and its great glasshouse. No side shows tempted us: we shouldered our way through the holiday crowds to the filling ground to find the men in charge blowing up the monster balloon for its trial trip. “My aunt”, said George, – a very favourite expression of his, “but what do you feel like now?” By this time the unwieldy creature was swaying backwards and forwards overhead, straining at the ropes that held her, and the car looking the frailest place of safety under the circumstances. “ Oh well it’ll be alright when we are once down again” said I, “in for a penny, you know, and we shall get a good view, see Kings Cross perhaps, and all the places we’re used to” but my heart was sinking. “ Now gentlemen!” shouted the proprietor through a fog horn “ Jump in and we take the money on board, – no vittles or drink allowed, as we shall be back in half an hour!”. But the people wanted a lot of coaxing and unaccountably hung back. The man caught sight of our faces, upon which a fearful joy and expectancy was painted, and started again to harangue. “Here are two to start with” he shouted and almost bundled us in. The people grinned, but didn’t follow us, and sooner than lose any more time, and mentally meaning to give us a short journey, he and the man jumped onto the car gave orders for the ropes to release her and away we went. But at the moment of mounting, to our dismay, one of these men with incredible swiftness swarmed down the side of the car and dropped to the ground, and we shot up. “What is the meaning of this?” cried George and we weren’t left long in finding out. The man’s face was white with rage. A jeering shout was sent up, and looking overboard we discovered that the captive rope was severed, and with its end trailing beneath us the balloon was rising with ever increasing velocity towards cloudland and the sky beyond. We were thunderstruck and turned to the ‘Captain’ for explanation or help of some sort. But to absolutely no purpose. He was dazed with fright – or something stronger, and muttering something about “His mate Bill” and that “he’d be even with him yet,” he sank in a speechless heap on the floor of the car and there remained. We looked at each other in amazement. The minutes went by without either of us speaking, but at last, with as equable heads and hearts as we could manage we proceeded to take in the situation. Up above us the great swaying canvas was shouldering the wind, the breeze singing through its cords, as the car cleft its path through the sunlight and blue sky that lay about us. Below was the kindly earth and safety, the vanishing Palace and its thousands shining through the simmering haze of heat. The practical problem emerged. “Chance it”, said I, and taking a pendent cord in our hands we pulled for all we were worth. Out with a hissing and roaring rushed the gas and we descended – too quickly indeed for our breathing powers. We held her up and looked over to see if any bearings were available. Yes, there towards the south west was a town, Croydon we thought, and knew enough not to come down amidst bricks and mortar: so having let the valve go, we looked about for ballast. Nothing to be had. The only thing we found was some bread and butter and cold tea. We weren’t too upset to appropriate this, and without any scruple, but there was nothing to throw out. Luckily the wind kept us moving south west, and at a safe height. On we went, the first feeling of not unnatural alarm giving way to a certain fearful joy at our extraordinary venture. We could see people gesticulating at us, trains running about like little white tailed rabbits, houses and buildings looking all too funny from our standpoint, and the immense sweep of landscape all round us. “Well” said George at last, “how long is this to last, think you? And what will they do at home? We must get out of this somehow.” “ I’m agreeable”, was my reply “so long as we don’t land in the sea”. “Oh stow your jokes”, said George “and say what we’d better do with this snoring hulk”, and he prodded the ‘Captain’ with his foot. He only grunted. If we could only have got from him his story, and why his partner had played such a wicked trick it would have been something. Presently we could see the houses thinning and the country becoming more open, and at no very great distance some farm buildings.

“Here goes”, said George, “I’ve got a good idea”: and with that he set to work to haul in the captive rope. I joined him hand over hand. “ Now then, let the gas go and tie this old fellow up”, said he. And that’s exactly what we did do. All unresisting the ‘Captain’ let us coil that rope round him from head to foot, making it fast about his middle. The wind dropped, the gas escaped, and we descended gently for a farmyard. Coming within hailing distance, the shouts of labourers reached us, and making an arch of our hands, we trumpeted “ Hullo there, where are we?” Back came the ready answer: “Why, you’re in a ballune, bor!”. Which wasn’t exactly what we wanted but it served to make them merry. “Well, catch then” shouted George. And using all our strength we hoisted the ‘Captain up to the edge of the car and slowly payed him over. That did it, down, down he went till within a yard or two of safety, all the yokels expectant, – when the balloon gave a lurch, our muscles relaxed, and bang he went into a pond among some ducks. “That will wake him” said George. There were plenty of willing hands about us now. The ‘Captain’ was a fine makeweight; the rope was laid hold of, and when within sight of twenty yards, we didn’t wait for a second venture, – no we didn’t, we swarmed down that rope quicker than usual and then for the first time critically took in the dimensions of that balloon. We explained matters to the open-mouthed farmer, saw to the deflation of our airship, and having sent a line to the Palace authorities as to where they would find the man and his charge, railed it home.

“Well” said George, that evening at supper, “ Carey and I are jolly hungry I can tell you, but Charlie, I’ll tell you a story afterwards.” “ Oh bother!” was Charlotte’s reply, looking up from a Miss Young. “You’ve said that so often: you’ve only learnt some more poetry and want me to hear you.” “No, no” said I, “ It’s not poetry this time, – you listen.” …..She listened, and in the waning hours, when “night’s candles were burning out” and the casement was a glimmering pane, Aunt Charlotte was still listening, but Uncle Fred (the youngest at home then) who began well, had to be carried to bed at half time. He hears the story now, perhaps for the first time, after many days.

xxxxxxx

Carey Linnell Palmer became a master printer at 23 Jesus Lane, Cambridge. His brother George went on to be a clergyman and Doctor of Music. The ten year old ‘Uncle Fred’ who fell asleep during the narrative, succeeded his father and elder brother to become the proprietor of the Church Times.

Like this:

Like Loading...