by The Curious Scribbler

I enjoyed an invigorating winter walk around Llyn Eiddwen, the natural upland lake which lies between a grassy windswept ridge and the wooded Mynydd Bach. Sometimes migratory swans Whoopers or Bewick Swans can be seen there in winter, though none were to be seen when I visited on 30 December.

Last march I saw five migratory swans on Llyn Eiddwen

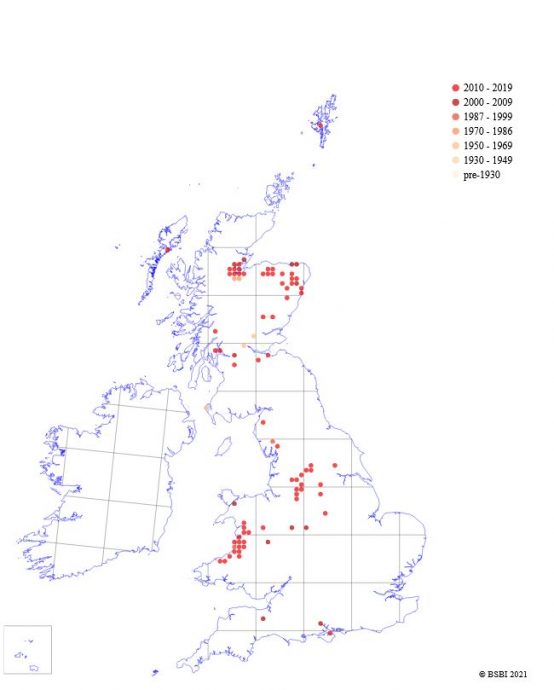

We began our walk at the monument to four local poets which stands above the dispersed community of Trefenter. Here the wind whistles in from the west and the land drops away to the distant sea. One of the four poets lived in Llanrhystud, the village visible from this altitude nestled close amongst the patchwork of fields and hedges, another grew up in Blaenpennal, and a third in Trefenter. Their names are J.M. Edwards 1903-1978, B.T. Hopkins 1897-1981, F. Prosser Rees 1901 -1945 and T. Hughes Jones 1895-1966. I must learn more of their work.

The plaque on the monument

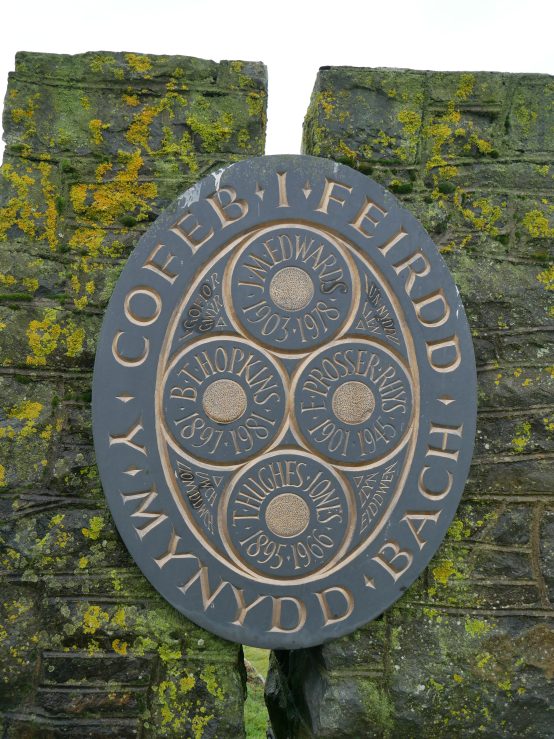

There are ruined cottages along the western shore of the lake and broad stone walls topped with gnarled beeches and sycamores which outline the former gardens and the rough road connecting them. I wonder in what proportion the lake and the Crown common land around it provided the livelihoods of these former inhabitants, and what led to the abandonment of these well-built cottages. I imagine though, that they may have still been occupied in 1879 when local men were employed to build what became known as Tredwell’s Castle in the lake.

A ruined cottage east of LLyn Eiddwen

Mark John Tredwell (b. 1856) was a rich young orphan who was brought up principally by his grandmother, educated briefly at Cheam and Harrow and who, for some unknown reason decided, on inheriting his parents’ wealth, to settle and lure his many friends to Ceredigion. In 1878 he took a 21 year lease on the small Georgian mansion Aberllolwyn at Llanfarian and spent freely on both house and garden, building cabins in the grounds to accommodate the parties of friends who arrived on the train and were conducted out to the mansion by charabanc. He created a small menagerie, apparently including a monkey, a bear and numerous ornamental birds. He threw lavish parties for his guests, and also for the local school and Wesleyan chapel. However this was not fun enough and led to his craziest investment – a party castle on a man-made island in Llyn Eiddwen, on land he didn’t even own.

The ruin of Tredwell’s Castle on Llyn Eiddwen

In the mid 20th century the ruined Tudwal’s “castle”, sketched by E.T. Price of Llanrhystud, was in better shape

Locals were employed quarrying the necessary stone and it is estimated that at least a thousand loads of stone, lime and timber were transported by rowing boat across the 100 yards of water to the masons building the perimeter wall, the tower and some ancillary sheds and buildings.

An account in the Aberystwyth Observer on 12 July 1879 describes a crowd of people who assembled at the railway station to view Tredwell’s latest purchase, a steam powered launch capable of carrying up to six persons. Apparently it took 20 horses to drag it to Tredwell’s ‘pool in the mountains’.

In the summer of 1879 party guests were accommodated at Tredwell’s expense at the prestigious Queen’s Hotel on the promenade, then transported by charabanc and steam boat over to the island, where the entertainments were raunchy in the extreme. Orgies were mentioned, and local lasses were said to be involved.

Unfortunately for him, Tredwell’s considerable wealth was insufficient to the the project, bills went unpaid and after a lengthy and expensive court battle with his builders he was declared bankrupt. The lease on Aberllolwyn was terminated in 1881 and he eventually died, penniless, in London in 1930.

There is no local folk memory of the steam launch so it may have been repossessed, or perhaps it lies under the waters of the lake. The ruined square tower on the island still stands surrounded by willow scrub, and the evocative emptiness of the landscape is enhanced by the ruined cottages on the shore.

Ruined Cottages on the shore of Llyn Eiddwen

On my recent visit an equally compelling mystery was the glistening gloops of jelly on the pathside where the path runs parallel with the shore. I am told these are Crystal Brain Fungus Myxarium nucleatum, a fungus ( but not a mushroom) which is found in winter during wet weather and when dry shrivels up to just a rubbery patch. But if that is so, what is the jelly for? Does it spread spores? It just appears to cling to the rocks and grasses, in lumps up to 4 inches across, glistening in the winter sunlight.

Crystal Brain Fungus

Crystal Brain Fungus

Clearly there is much more for me to learn both about the work of the four poets and about these Crystal Brains strewn upon the grasses.