by The Curious Scribbler

There has been quite a lot of publicity this summer about Carreg Llwyd, ( Google ‘Mark Bourne Wales’ for a selection: the Daily Mail, the BBC, Wales Online, and even The Times ran articles this summer).

The story concerns the extraordinary scale models built by writer and chicken farmer Mark Bourne, who died about ten years ago. Some will remember his many contributions to the Cambrian News and Country Quest. His remote garden on a terraced slope near Corris has become dilapidated and overgrown and The Little Italy Trust has recently been set up to preserve it. Jonathan Fell, gardener and conservator showed me round.

A medley of Italian buildings climb the mountainside

Looking up from the adjoining footpath one sees an amazing medley of model buildings, their facades facing westward, marching up the slope, fading away into the dense conifers above. Nearest to the house is a signature piece, The Duomo in Florence, just four feet tall and neatly labelled with an inscribed slate slab reading Santa Maria del Fiore. Nearby, ascending from the top of the boundary wall are the Spanish Steps from Rome. These and every other garden feature have been fashioned out of concrete, often impregnated with pigments to mimic the warm tones of southern Europe. There are palazzos, churches and towers, mostly palladian and always clearly labelled, often like a guide book with architect and date, which you approach by a labyrinth of concrete paths and steps. Interspersed are a number of breeze-block and corrugated-iron stores and workshops in which the creative process took place. Timber moulds and formers were built to imprint the decorations, and reclaimed objects, chickenwire, hub caps, dustbins, bottles, washing machine drums and bedsteads often form the basis of these three dimensional structures.

Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence

It is certainly true that about thirty of the models are of famous Italian buildings, and that Mark Bourne and his wife Muriel holidayed regularly in Italy, taking photos and making drawings which were then copied in concrete at home in Wales. It rains a lot in the mountains, and no doubt when the concrete would not set he had plenty of time to inscribe the calligraphy on the slate plaques which adorn each piece. But there is much more than Italy represented here. Rather, it seems that while Mark Bourne might have written an article, or I a blog on a subject which caught our interest, he instead committed it to concrete.

Randomly perched among the models, and all labelled, are the Brick Kiln at Amlwch, Anglesey, the Nash Lodge at Attingham Park, Boyana Church at Sofia, Bulgaria, and the worlds longest brick bridge, the Goltzsch Viaduct which takes trains from Mylau to Netzschkau in Germany.

‘World’s largest brick bridge. 26,000,000 bricks’. Jonathan Fell surveys the garden.

A model of York Minster and accompanying plaque marks the accession of Rowan Williams as Archbishop of Canterbury. Another plaque list the names, ages and occupations of the occupants of Carreg Llwyd as recorded in the 1841 and 1851 censuses. When Mark Bourne wanted to remember something, he did not make a note, he made a model.

People gave him stuff which he incorporated into the garden. Pieces of architecture, concrete urns and figures, and Victorian bricks. One friend, John Oliphant, gave him an entire brick collection, and many of these are built into a wall visible from the passing footpath, set on their sides to display the lettering on the bricks. Farther up the same path Mark mounted a concrete geological relief map of north Wales into the wall.

A small part of the John Oliphant Brick Collection

Someone else gave him a bit of artificial stone salvaged from the cargo of the Primrose Hill, a vessel which foundered with great loss of life, on South Stack, Anglesey in 1900. A complex slate memorial records the story.

And somehow he became the owner of a great many tiny bricks. They are built into small didactic walls demonstrating different bricklayers’ patterns. Where else can one find labelled examples of Flemish Bond, Stretcher Bond, English Bond, Header Bond and Garden Wall Bond?

Exemplars of five types of brick wall ( and an old bedstead)

Carreg Llwyd is certainly unique, a monument to one man’s creativity, but what is its future? Its tourist potential is limited. It is up a steep footpath away from the nearest road and there is nowhere to park within a mile. Once one arrives it is perilous, for the paths, the terraces and some of the buildings are beginning to collapse, ( the Leaning Tower of Pisa is already just a memory.)

Some structures have already collapsed and others are at risk.

Concrete formed upon corroding metal has a limited life, and the whole project though impressive is crudely executed. It is magical to stand among the crumbling ruins, overreached by rhododendrons, briars and sapling trees, scraping away the moss to read more of Mark’s explanatory calligraphy on slate. One can also see where once there were vegetable beds, roses, cats’ graves, a little lawn and water channels flowing through the grounds. But this very personal space was built by hand (and prodigious amounts of cement), by one poor but passionate amateur, who was still adding to his oeuvre at the age of eighty. There is no place or access for the machines which might repair its inherent faults. To achieve maintenance would require the services of a full-time hermit.

A former flower garden among the ruins

Every space within the plot has been adorned with models

A vertiginous view of turrets and workshops from above

This is the ultimate secret garden – most people who come across it by chance feel it is their personal discovery. Even were it fully repaired and made safe it could take only a tiny number of visitors at any time. Its plight perhaps bears comparison with Derek Jarman’s shingle garden created around a modest shack in the shadow of the nuclear power station at Dungeness, Kent. Last year it was announced that the crowdfunding led by the Arts Council had raised £3.5 million to preserve it, and that artist residencies and very limited visiting opportunities will follow.

But Derek Jarman was a famous film director (and gardener) with many influential showbiz and artist friends. Mark Bourne, throughout his lifetime, was a very private man.

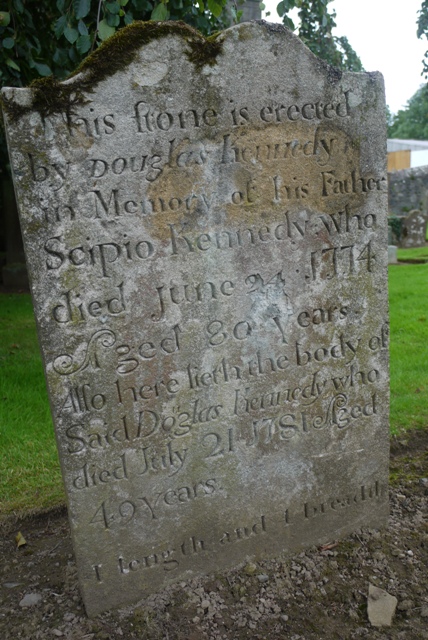

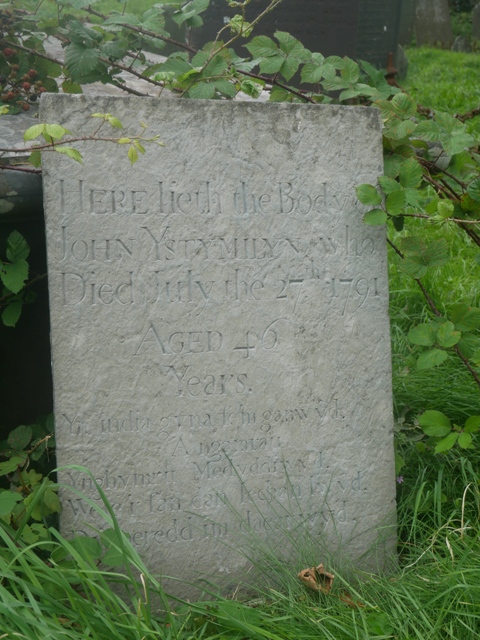

The local girls certainly thought so, and are said to have competed for the favours of the exotic gardener. One such was Margaret Gruffydd, another servant in the household who later moved to a job near Dolgellau. Having run away to get married to her, John lost his post at Ystumllyn but the two were clearly employable: living at Ynysgain Fawr they produced two sons and five daughters, but eventually moved back to work for the Wynnes at Ystumllyn. He died quite young, suffering from jaundice, aged 46. The pamphlet identifies the marriages of several of his daughters, who may well have descendants today. One son, named Richard, grew to adulthood and became Lord Newborough’s Huntsman at the Glynllifion estate. He is remembered as a ‘tall, calm man, who wore a Top Hat, Velvet Coat with a high white collar around his throat’. He had a family and lived to the age of 92.

The local girls certainly thought so, and are said to have competed for the favours of the exotic gardener. One such was Margaret Gruffydd, another servant in the household who later moved to a job near Dolgellau. Having run away to get married to her, John lost his post at Ystumllyn but the two were clearly employable: living at Ynysgain Fawr they produced two sons and five daughters, but eventually moved back to work for the Wynnes at Ystumllyn. He died quite young, suffering from jaundice, aged 46. The pamphlet identifies the marriages of several of his daughters, who may well have descendants today. One son, named Richard, grew to adulthood and became Lord Newborough’s Huntsman at the Glynllifion estate. He is remembered as a ‘tall, calm man, who wore a Top Hat, Velvet Coat with a high white collar around his throat’. He had a family and lived to the age of 92.