By The Curious Scribbler

This is a good acorn year and in the last few days the green acorns have begun dropping, leaving empty acorn cups on the oaks. They are very pretty scattered on the dark leaf-mould before they turn brown; smooth light green egg shapes, cream-coloured at the base where they were enclosed in their cups.

It has also been a bumper year for the Knopper Gall. I first noticed this a fortnight ago on my regular walk along the cycle path from Rhydyfelin to Llanfarian which is margined by a number of small and medium sized oaks. Under certain trees there was a carpet of crunchy brown detritus on the path, while under others there was very little. Few acorns had yet fallen, and those which had been displaced by wind were still nestled in their acorn cups. It was not acorns, but Knopper galls which crunched under my feet.. These sculpted perversions, born on an acorn petiole, turn brown and are shed by the tree in advance of acorn release. There is already a hole in the distal end where the author of the Knopper gall has escaped.

Knopper Galls, Rhydyfelin

Knopper galls are formed in place of acorns through the efforts of a tiny parasitic wasp, Andricus quercuscalicis. The name derived from the German ‘Knoppe’ the name for a 17th-century felt cap or helmet which by virtue of its parallel external seams has a similar appearance. Chemicals released from the developing wasp egg completely re-programme the developing acorn so that instead of either acorn or its cup, a Knoppe of similar size grows in its place.

There a number of different wasp species which promote galls on oak trees, but the Knopper Gall is a recent newcomer from Europe which was first noticed in England in the 1950s and in our county was apparently first recorded at Llanilar in 1982. ( see Arthur Chater’s fine volume Flora of Cardiganshire.) The wasp’s life cycle is complex and takes two years and two different species of oak to complete. The wasps which emerge from a hole in the end of the gall are all females which must seek out a Turkey oak Quercus cerris in the spring. There they lay eggs in the male catkins which produce small conical galls. In these little galls both male and female wasps develop. These wasps mate and the fertilized females then seek out the English oak Quercus robur in which to pervert the development of the future acorns.

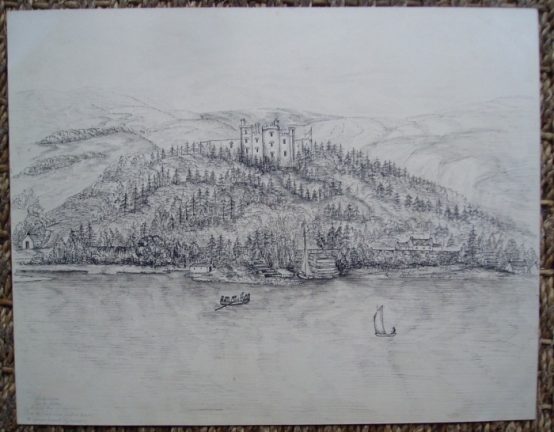

Our native oaks in Ceredigion are the Sessile Oak Quercus petraea, so-called because its acorns sprout directly from the twig, and the Pedunculate Oak Quercus robur which bears its acorns on stalks up to an inch long. There is also a hybrid between the two: Quercus x rosacea. The Turkey Oak by contrast is non-native, and best known for the specimen trees planted in parks and gardens in the last 250 years. The finest in the county was, until its recent felling the huge oak above the parapet of Cardigan Castle. There are some big trees at other big houses, such as Monachty, Trawscoed, and Plas Cwmcynfelin. It seems a long way for a 3mm wasp to fly, though I am told that the acorns are commonly self sown so there may be young Turkey oaks lurking unobserved in woods and hedgerows nearer by.

Close inspection showed that my heavily infested tree was indeed Quercus robur, its few remaining acorns born on long petioles. Some of the other trees in the hedgerow definitely had sessile acorns and were unaffected. Others had shed a smaller crop of Knoppe Galls, – perhaps these trees were the hybrid? The Sessile oaks however did not escape all kinds of attack. Under several trees there were significant numbers of Artichoke Galls, caused by another species of wasp Andricus foecundatrix, which perverts the leaf buds into acorn-sized replicas of little globe artichokes. This wasp needs only our native oaks to survive.

Artichoke Galls, Rhydyfelin

Also beneath one tree I found a few marble galls, – the size and shape of small marble 1cm in diameter – the work of yet another species Andricus kollari, which needs both Quercus robur and Quercus cerris to complete its life cycle.

Marble Galls, Rhydyfelin

Now I look out for oak galls wherever I go. Last week I was in Ireland and and at the grand historic garden of Kilruddery, in county Wicklow, I found a Pedunculate Oak heavily infested with Knopper Galls, some still sticky and slighty green in the gentler climate. On the nearby lawn stood a fine Turkey Oak awaiting a visit from the recently emerged wasps.

Knopper Galls at Kilruddery, Co Wicklow

A handsome Turkey Oak at Kilruddery, County Wicklow

At Hafod, by contrast, there are many Sessile oaks and not a Knopper Gall to be seen. I don’t know the whereabouts of a Quercus robur at Hafod, but even if there were one it would possibly be an arduous flight into the uplands for a tiny wasp hatched in a Turkey Oak nearer the coast. Undoubtedly though, Andricus quercuscalicis is still expanding its range and this warm summer has provided perfect conditions not just for butterflies but for this parasitic wasp.