by The Curious Scribbler

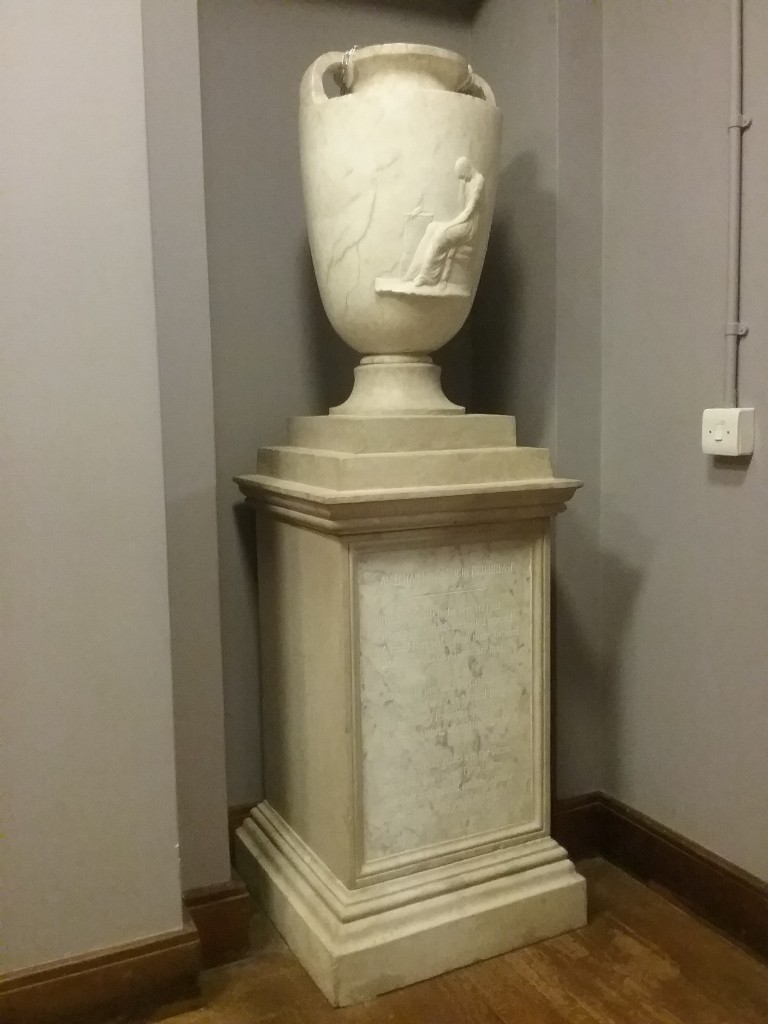

I chanced recently upon on Mariamne’s Urn at its latest location in the National Library of Wales. It stands in a passage adjoining the door to the disabled toilet, secured by substantial metal chains through its amphora handles, but devoid of any labelling whatever to explain its signifiicance.

It is a large white marble funerary urn standing upon a square plinth. Two hundred years ago it graced Mariamne Johnes’ private pensile garden on an outcrop above the Ystwyth at Hafod. This garden was, according to Thomas Johnes’ correspondence, created for Mariamne by his friend the Scottish agriculturalist Dr Robert Anderson in 1796, when his daughter would have been aged just twelve. In a letter of some hyperbole he then wrote to Sir James Edward Smith “The pensile gardens of Semiramis will be a farce to it, and it will equally surprise you as it has done me. I am very well satisfied with my Gardener, and trust everything will go on well.”

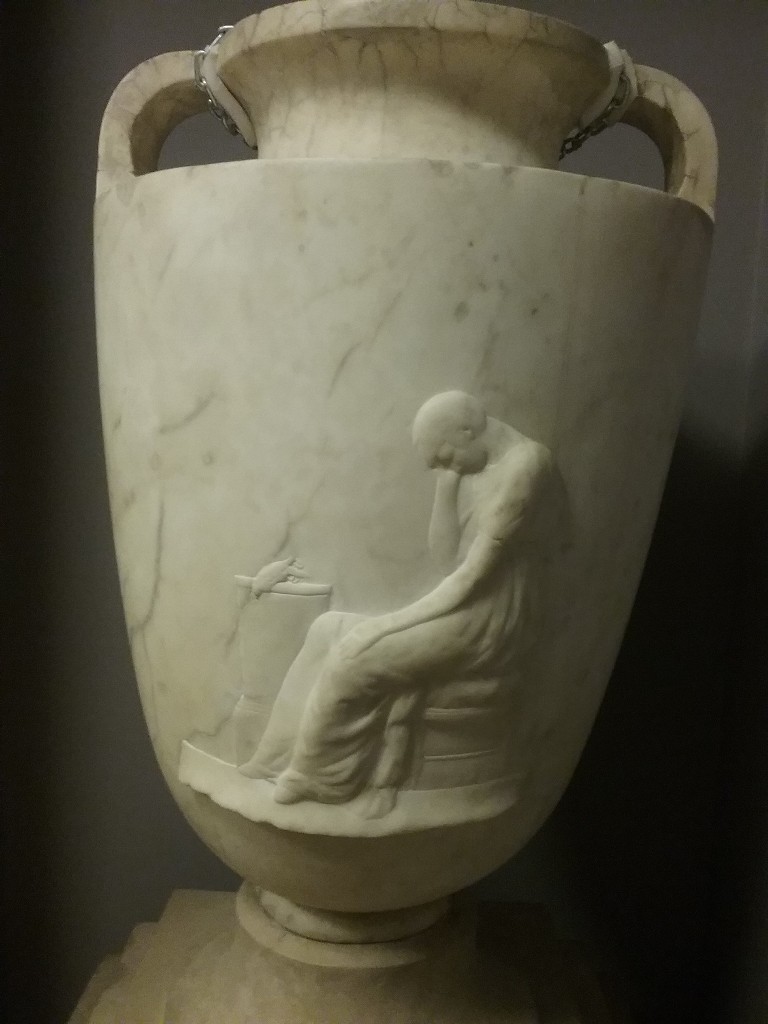

The young Mariamne showed a precocious enthusiasm for botany and corresponded with leading botanist Sir James Edward Smith. Her private garden became a showcase for shrubs and alpine plants, although there must have been periods during her adolescent illnesses when she could scarcely have visited it herself. She died, aged 27 in 1811. The urn, a work by celebrated sculptor Thomas Banks, is generally believed to have been created in 1802. Banks had made other sculptures for Thomas Johnes: Thetis dipping the infant Achilles into the Styx, busts of Jane and Mariamne, a fireplace for the mansion. He was at Hafod as Johnes’ guest in September 1803, when Johnes recorded that he was now disabled in one arm by a paralytic stroke. On the face of the urn is a bas relief depicting a limp maiden mourning beside the body of an equally limp and rather more dishevelled small bird, dead on a small pedestal.

The Robin Urn by Thomas Banks, in a corridor in the National Library of Wales

On the plinth is a three verse poem by Samuel Rogers, – I have transcribed the verses with original capitalisation, from the plinth itself.

An Epitaph on a Robin Redbreast

Tread lightly here, for here tis said

When piping Winds are hush’d around

A small Note wakes from Underground

Where now his tiny Bones are laid

No more in lone and leafless Groves

With ruffled Wing and faded Breast

His friendless homeless Spirit roves;

Gone to the World where birds are blest

Where never Cat glides o’er the Green

Nor Schoolboys giant Form is seen

But Love and Joy and smiling Spring

Inspire their little Souls to sing.

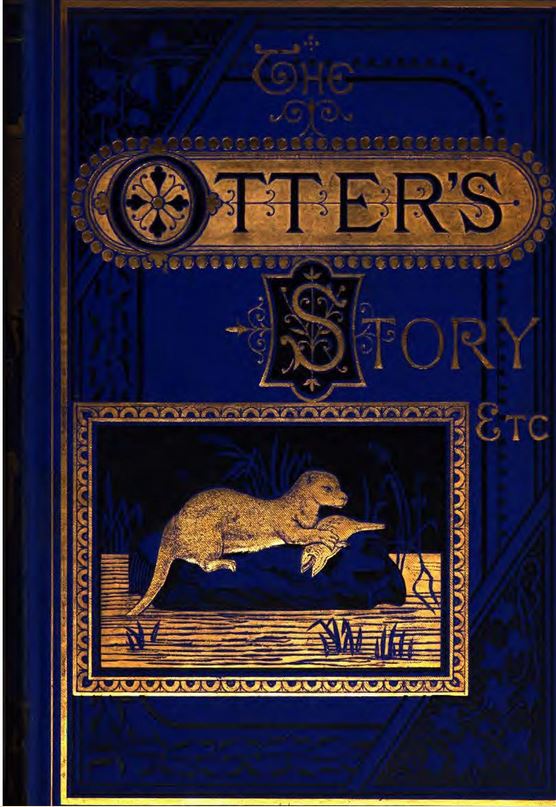

It has been customary to imagine that this sentimental outpouring was dedicated to a particular pet robin, and Mariamne’s attachment to it. This has been claimed in Elisabeth Inglis Jones’ book Peacocks in Paradise. But on reflection, and in the light of a perusal of the other, now seldom-read works of this once well-known poet and arbiter of taste, I believe it to be a more generic sentimental verse. Samuel Rogers’ first long poem in two parts, The Pleasure of Memory published in 1792, shows a sentimental preoccupation with the romantically remembered past, the village green and a lonely robin. I quote few couplets:

Twighlight’s soft dews steal o’er the village green

With magic tints to harmonise the scene

Or strewed with crumbs yon root inwoven seat

To lure the redbreast from his lone retreat..

…Childhood’s lov’d group revisits every scene

The tangled wood walk and the tufted green.

Certainly there are few gardens less likely than Mariamne’s remote crag to be troubled by either schoolboys or cats!

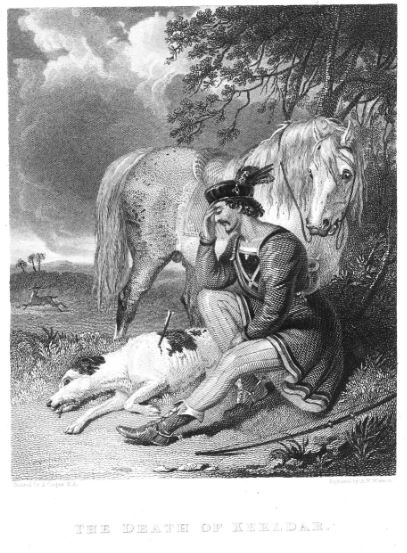

Is this really Mariamne, mourning her pet robin?

Rogers has not enjoyed lasting fame as a poet, but he was a major force in the literary social life of London in the early nineteenth century. He published and republished his poems in many editions between 1792 and 1834, with engravings of pictures by Thomas Stothard and by W.M.Turner. He was clearly very proud of his early works, for both The Pleasure of Memory, and The Epitaph on a Robin Redbreast appear in editions from 1810 to 1834. In both these editions a footnote to the Epitaph states “Inscribed on an urn in the flower garden at Hafod”. I suggest that Rogers did not visit Hafod, and was unaware of the distinction between Mrs Johnes’ publicly acclaimed flower garden, and Mariamne’s private garden. However Elisabeth Inglis Jones, writing in 1950, evidently recollected the urn in Mariamne’s garden, where she described it as “overgrown with moss and ivy, almost lost among encroaching trees and bushes, it was still standing where [Banks] placed it one morning that September of 1803, nearly a century and a half later”.

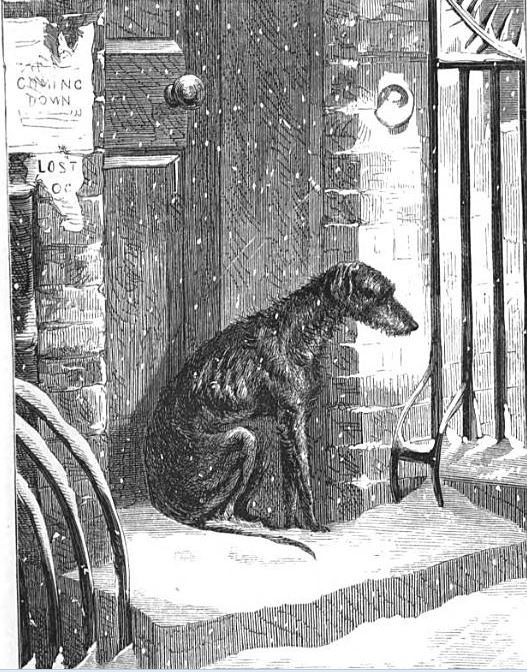

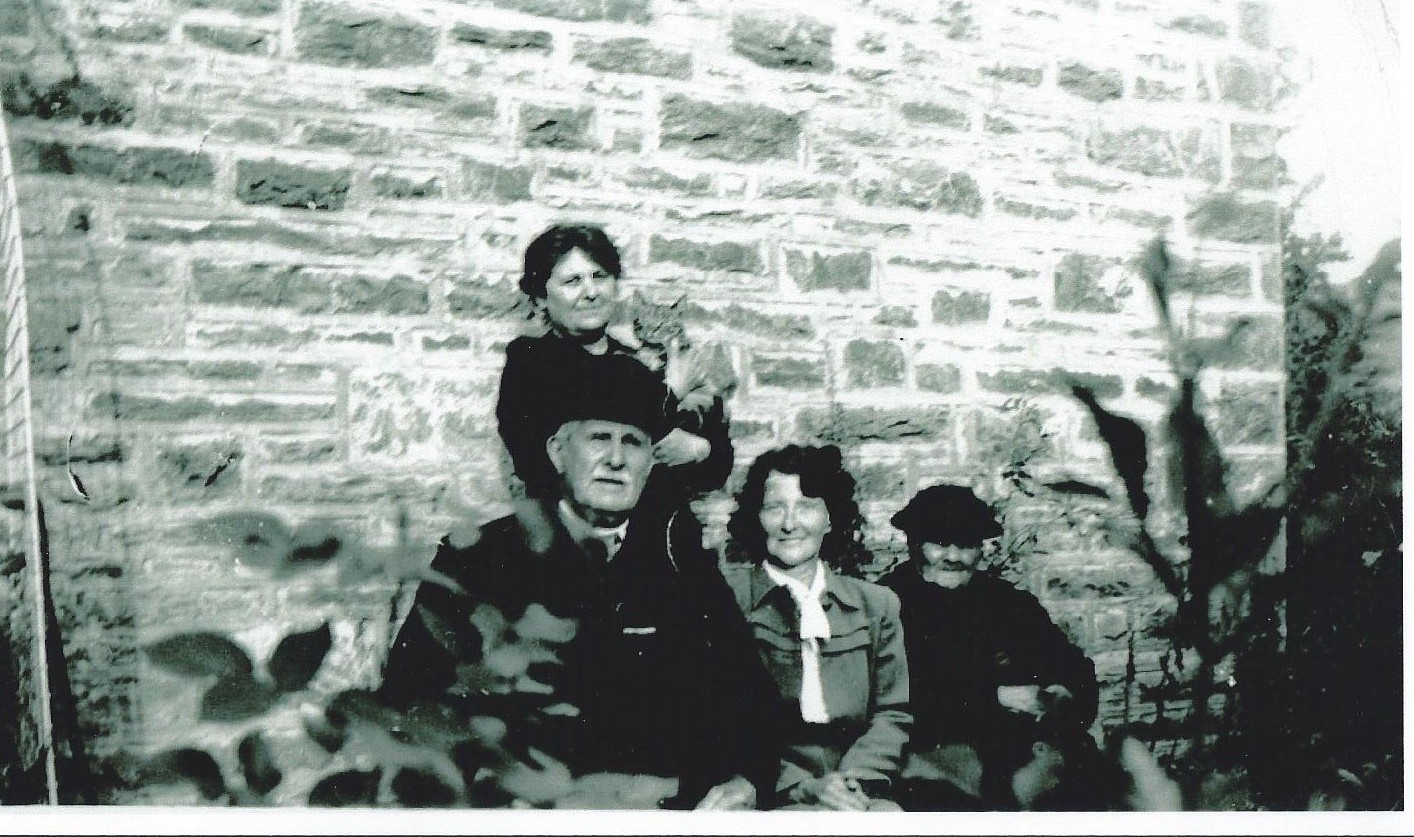

In the 20th century the fortunes of Hafod were in serious decline, culminating in the demolition of the house, with dynamite in 1958. The urn was purchased at auction by a relative of Jane Johnes, Major Herbert Lloyd Johnes of Dolaucothi and given into the care of the National Library. It was sited in 1948 as a garden ornament in the beautifully maintained rockery garden on the slope adjoining the caretaker’s cottage, marking the point where the footpath down to Llanbadarn and Caergog Terrace leaves the library drive. I am indebted to Dr Stephen Briggs for a copy of a photo of it in this location, in 1976.

The urn in the garden of the National Library of Wales, c. 1976. Courtesy of Dr Stephen Briggs.

A valuable piece, fears were expressed about the risk of theft or vandalism, and in the 1980s the urn was moved indoors, to a prestigious location on the first floor outside the Council Chamber. That is where I first saw it. But times change, and about 15 years ago it was moved into an atrium area of the extended library book-stacks. Here it was accessible only to library staff and was lost to general view. Perhaps its significance also became lost to common memory. Now shackled in the very antithesis of romantic chains, the urn, and an equally unattributed but rather attractive tapering marble plinth are tucked away, like fugitives, within recesses beyond a subterranean doorway. Only disabled members of the public and those seeking baby-changing facilities are likely to encounter it on a visit, and they will receive no clue as to its significance.

Mariamne’s urn is now in a corridor leading to the disabled toilets in the National Library of Wales (2016)