by The Curious Scribbler

I like to think I am quite observant but yesterday I discovered to my chagrin that I had been walking my dog regularly past the largest puffball fungus I have ever seen. To give it its proper name Calvatia gigantea must have emerged as a huge white blob in the depths of a bed of nettles late last summer. It would have been somewhat obscured by the growth around it until the nettles died back in winter. If I noticed it at all I suppose I must have dismissed it as a pale boulder lying on the surface of the field.

Then yesterday, after rain, my attention was attracted by a big irregular brown object, beaded with raindrops and with a fragment broken away at one side. Too big to be a poo of any known animal, but with a strangely smooth internal texture. I poked it with a stick, expecting it to be hard. Instead is proved to be extremely soft and light, and rolled away at a touch.

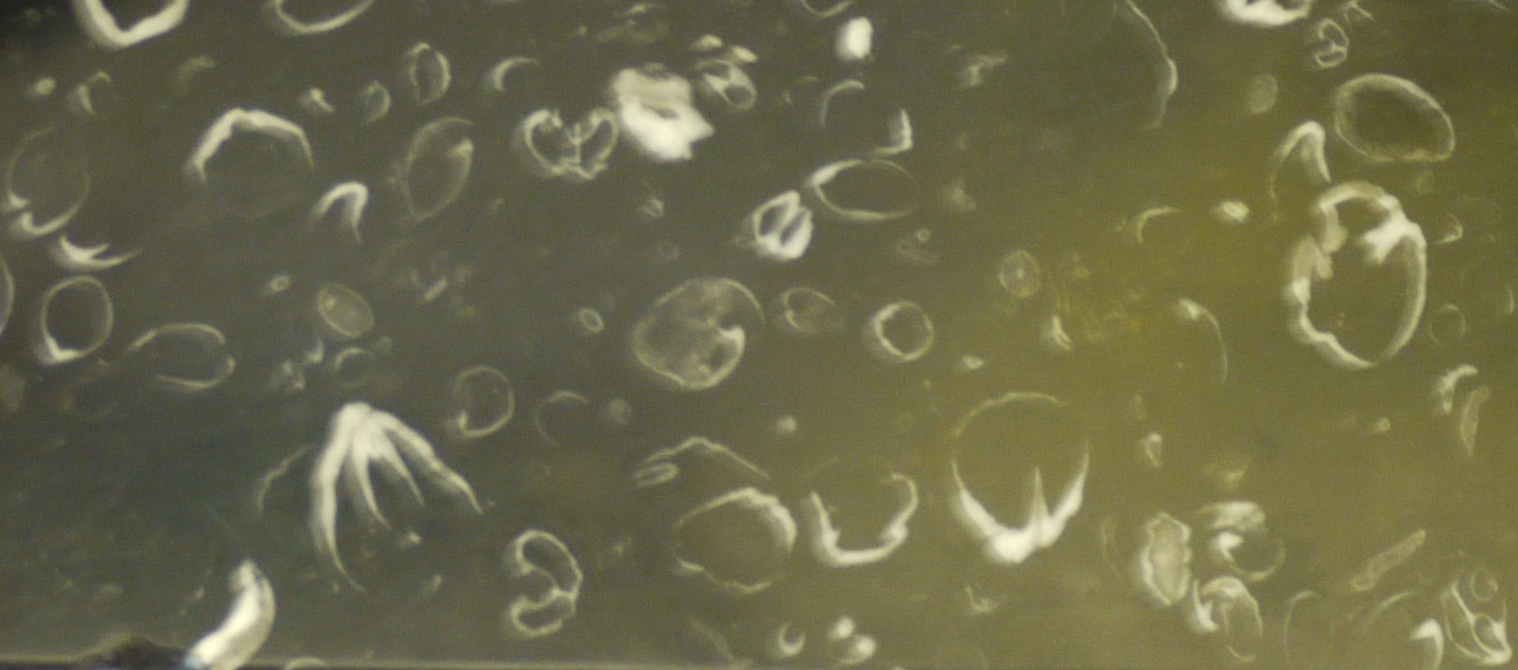

This fruiting body or gleba contains literally trillions of spores, ready to be released into the wind. It grows from the underground mycelia with a narrow neck which eventually breaks allowing it to roll around like an oversized football. I found the patch of bare earth nearby where it has until recently sat, like a large stone, inhibiting the grass roots underneath. It is cleverly designed by nature to stay dry so that the spores can blow away. The fungus is so water repellent that the rain stands in tight globular droplets on the surface. The leathery skin which formerly contained it has peeled away except on the lower surface.

Water droplets bead the upper surface of the giant puffball

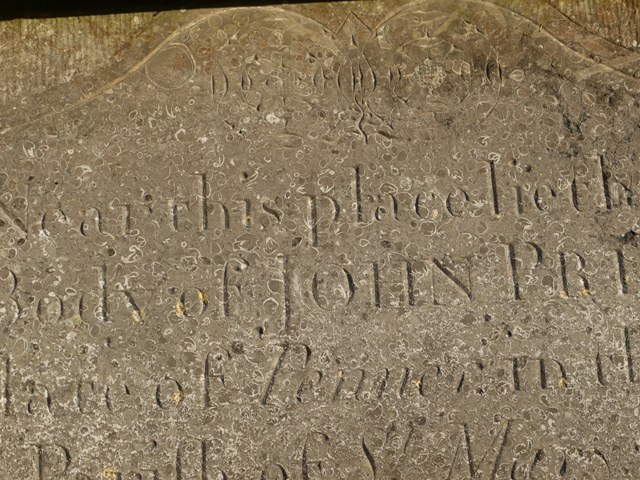

The under surface of the puffball

Far lighter than a loaf of bread and as soft as a sponge we lifted it and turned it over to admire its form. Tapping any part of it with a stick released clouds of spores into the air.

Calvatia gigantea releases millions of spores into the air

This remarkable fungus would have been edible if I had spotted it in summer when it was firm and white. Now mature and brown it has no culinary use, but I have read that the mature spongy material used to be sliced into layers and used for wound dressing, especially for veterinary purposes. It was valued for its styptic effect, stopping bleeding and encouraging coagulation. This 18 inch monster would dress quite a few wounds.

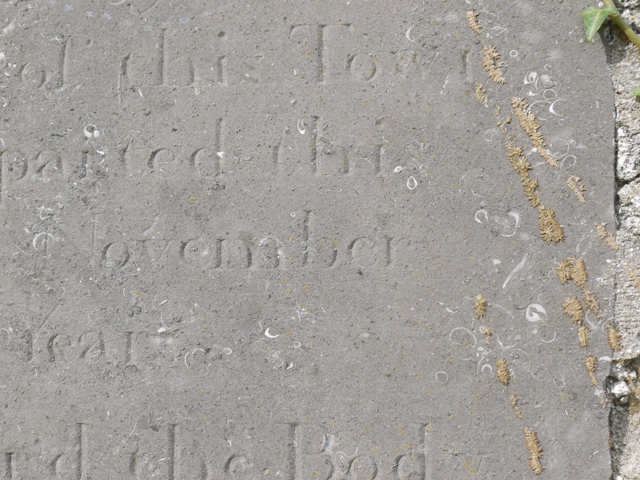

I found a second much small puffball still in situ nearby. The thin leathery skin had only just started to peel away from the upper surface to reveal spore tissue beaded in water. Where the skin is intact, the water just runs off it like a gaberdine.

A much smaller giant puffball still mainly covered with its waterproof skin

Surprisingly little is known about giant puffballs. They occur rarely and unexpectedly and even where they have been found another may not be seen for many years. It is thought that they perhaps take their nutrients symbiotically from the grasses or other plants, rather than saprophytically from rotting wood. They are not found amongst trees. The underground network to produce this huge growth must be substantial. We know very little about these fungal networks.

The excitement of finding my gigantic puffball is matched by another winter mystery, the Crystal brain fungus or star jelly I wrote about last year. A number of local people have posted pictures of this material recently. We may be exploring space, but we still do not know exactly what these gelatinous masses are and whether they come from fungi, meteor showers or vomited frogs.