by The Curious Scribbler

I recently visited the tiny rural church of St Cynhaearn, which stands within a circular graveyard in the middle of nowhere between Porthmadog and Criccieth. Worshipers must have walked to it from Pentrefelin and from isolated farms but when you stand at the church there is not a single house in view. Little wonder then that it is now in the care of the Friends of Friendless Churches. Fortunate for this lonely church and fortunate also for me, because since Covid the active churches have been strangely unwilling to leave their doors open. Friends of Friendless churches are the exception: they remain open all the time.

St Cynhaearn, Ynyschaearn

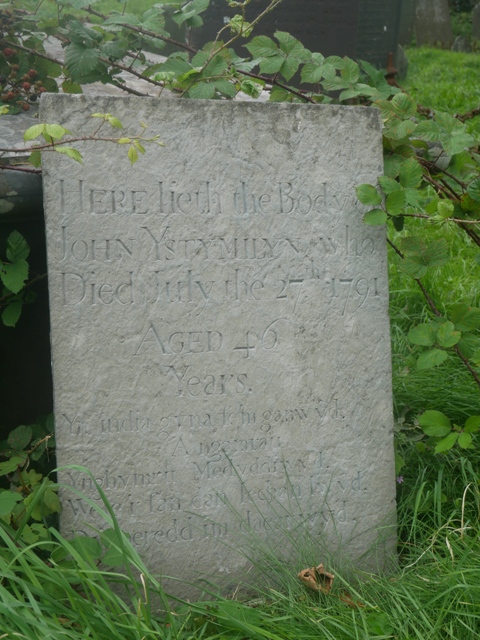

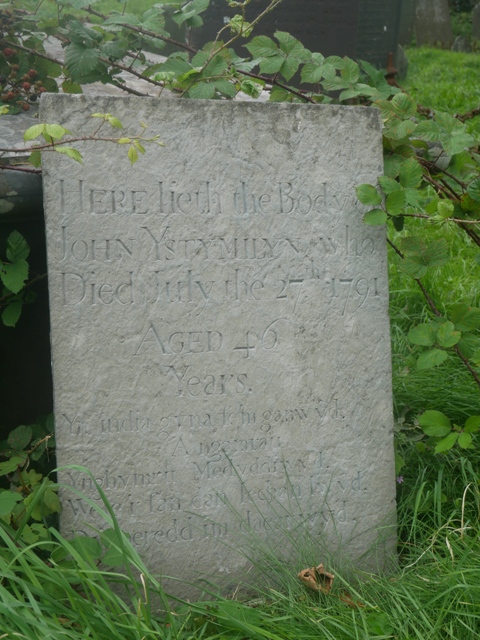

One objective was to see the grave of one of Wales’ early black inhabitants, John Ystumllyn, (1740-1786) who lies buried in the graveyard. His stone was soon located to the left of the path, propped against one of the many 19th century slate chest tombs. It seemed startlingly new-looking, clear even of encrusting lichen, but I suppose this is because it has recently been re-cut.

John Ystumllyn’s grave at St Cynhaearn

As I looked around it was clear that the eighteenth century memorials were carved on a locally sourced pale stone, quite different from the dark grey Penrhyn slates produced in the 19th century. The old local stones are not deeply incised and for the most part are barely legible. John’s fame perhaps justifies the facelift to the gravestone, but some of the romance has been lost with the restoration.

An unrestored eighteenth century gravestone in St Cynhaearn Church

Recut gravestone of John Ystumllwyn at St Cynhaearn’s Church

John’s life story was published in a welsh pamphlet by local bard Alltud Eifion of Tremadoc in 1888 and can be read in translation by Tom Morris 1971. The story is retold by Andrew Green in his blog Gwallter in 2017. According to an oral history originating from John himself, he was a child trying to catch a moorhen by a woodland stream when he was captured by white men who took him away to their yacht. His mother ran after them yelling in protest. It seems highly unlikely to me that he was ever a slave in the West Indies. He was simply captured in his native land to supply the fashion for a black servant in the grand houses of 18th century Britain. Such a trophy is best caught young to be trained for his new life. The account goes on to say that, on being added to the household of Ellis Wynne of Ystumllyn, he had no language and communicate only in howls and screams.

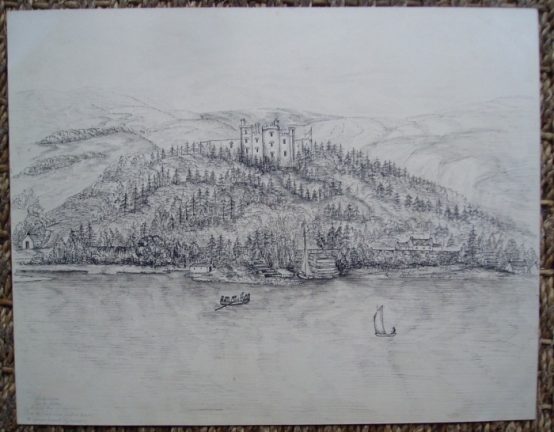

Ystumllyn, seat of the Wynnes in 1794 by John Ingleby

More likely he had no language that could be understood by his captors, for he seems to have been an intelligent boy. Alltud Eifion wrote: They had considerable difficulty for a long time in domesticating him, and he was not allowed to go out; but after some efforts by the ladies, he learnt both languages, and he learnt to write; then he was placed in the garden to learn horticulture, which he did more or less perfectly, as he was very ingenious.

In keeping with the status which their slave boy conferred, the family had his portrait painted and he is shown as a handsome young man.  The local girls certainly thought so, and are said to have competed for the favours of the exotic gardener. One such was Margaret Gruffydd, another servant in the household who later moved to a job near Dolgellau. Having run away to get married to her, John lost his post at Ystumllyn but the two were clearly employable: living at Ynysgain Fawr they produced two sons and five daughters, but eventually moved back to work for the Wynnes at Ystumllyn. He died quite young, suffering from jaundice, aged 46. The pamphlet identifies the marriages of several of his daughters, who may well have descendants today. One son, named Richard, grew to adulthood and became Lord Newborough’s Huntsman at the Glynllifion estate. He is remembered as a ‘tall, calm man, who wore a Top Hat, Velvet Coat with a high white collar around his throat’. He had a family and lived to the age of 92.

The local girls certainly thought so, and are said to have competed for the favours of the exotic gardener. One such was Margaret Gruffydd, another servant in the household who later moved to a job near Dolgellau. Having run away to get married to her, John lost his post at Ystumllyn but the two were clearly employable: living at Ynysgain Fawr they produced two sons and five daughters, but eventually moved back to work for the Wynnes at Ystumllyn. He died quite young, suffering from jaundice, aged 46. The pamphlet identifies the marriages of several of his daughters, who may well have descendants today. One son, named Richard, grew to adulthood and became Lord Newborough’s Huntsman at the Glynllifion estate. He is remembered as a ‘tall, calm man, who wore a Top Hat, Velvet Coat with a high white collar around his throat’. He had a family and lived to the age of 92.

The story has close parallels with that of one of my great great great great great great grandfathers, Scipio Kennedy. He too was a child captured in Africa, and he was brought to Scotland by a sea captain, as a gift for his daughter. This was some fifty years before John’s experience. Captain Andrew Douglas of Mains was not a captain in the transatlantic slave trade, but a naval officer, commander of a 60 gun warship which accompanied a convoy to Jamaica in 1702 and returned in 1704. He bought the young boy in Jamaica aged about seven and brought him back to his home.

Culzean in Scipio’s time

Three years later, when the captain’s daughter married John Kennedy, eldest son of Sir Archibald Kennedy of Culzean castle, Scipio was part of her dowry, and took the surname of Kennedy. In 1710, Sir John and his wife inherited Culzean castle, where Scipio was to spend his adult life.

Much is known about Scipio, (he has his own entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and a wikipedia page – he is Ayrshire’s first known black inhabitant). Sir John and Lady Jean invested ‘in his clothing maintenance and education’ and by his mid twenties he was a Christian, could read and write, and worked at Culzean. As a Christian he was now deemed a free man and in 1725 he signed a nineteen year contract to continue his employment with Sir John. This may well have included gardening, for Sir John was exceptionally keen on horticulture.

Like John Ystumllyn, Scipio was popular with the local girls, and in 1727 was severely reprimanded by the Kirk for fornication with another estate servant, Margaret Gray, who bore his child. They married in 1728, and had seven more children. The multi-talented Scipio served as butler in the Castle, and coordinated in his master’s extensive smuggling activities. He and his wife also wove and sold cotton and linen goods. In 1744 Sir Thomas Kennedy succeeded his father and built a substantial stone house for Scipio on a large plot in the grounds of the castle, the site of which has recently been excavated by the National Trust. Scipio was now smuggler, weaver and cook at the castle.

Estate survey showing Scipio’s house and land at Culzean (Image National Trust for Scotland)

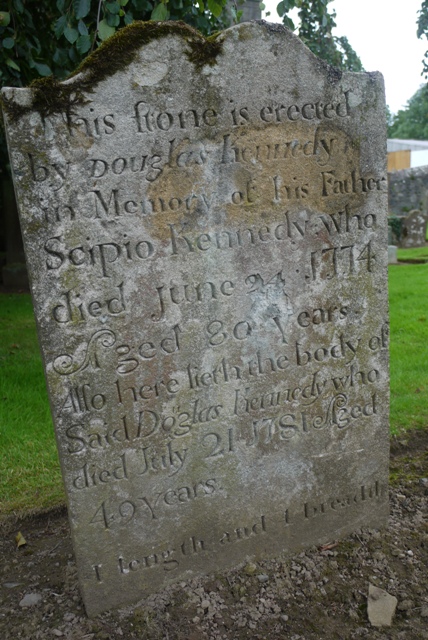

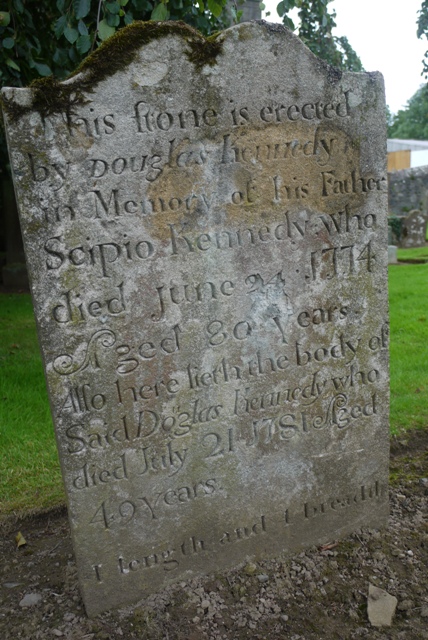

Scipio and Margaret’s eldest son Douglas continued in the family’s service and became the body servant of Sir John’s son Thomas Kennedy, accompanying him on his many European tours. Scipio lived to the age of 80 and is buried in Kirkoswald churchyard and a stone was erected in his memory by his son Douglas, who is also buried there.

Monument to Scipio Kennedy in Kirkoswald churchyard, erected by his son Douglas.

The National Trust at Culzean has issued a long series of blogs which agonize from today’s perspective as to the unknowable questions: Was Scipio oppressed? Was he unhappy? Did manumission significantly improve his life? Scipio’s manumission document rehearses his life story, in which he represents himself as very fortunate: ‘for as much as in my infancy I was bought and redeemed by Captain Douglas .. and was in a certaine way of being in perpetual servitude in the West Indies had it not been my happiness to fall into his hands purchased by his money with whom I remained for three years or thereabouts. At which time I was presented to Sir John and his lady …’

It was a lifelong commitment and when Lady Jean died in 1751, she left ‘to Scipio Kennedy my old servant, the sum of ten pounds sterling’ – which was the same sum she had earmarked for each of her grandchildren.

Scipio Kennedy and John Ystumllyn seem to have made a considerable success of their rudely transplanted lives.

Like this:

Like Loading...

The local girls certainly thought so, and are said to have competed for the favours of the exotic gardener. One such was Margaret Gruffydd, another servant in the household who later moved to a job near Dolgellau. Having run away to get married to her, John lost his post at Ystumllyn but the two were clearly employable: living at Ynysgain Fawr they produced two sons and five daughters, but eventually moved back to work for the Wynnes at Ystumllyn. He died quite young, suffering from jaundice, aged 46. The pamphlet identifies the marriages of several of his daughters, who may well have descendants today. One son, named Richard, grew to adulthood and became Lord Newborough’s Huntsman at the Glynllifion estate. He is remembered as a ‘tall, calm man, who wore a Top Hat, Velvet Coat with a high white collar around his throat’. He had a family and lived to the age of 92.

The local girls certainly thought so, and are said to have competed for the favours of the exotic gardener. One such was Margaret Gruffydd, another servant in the household who later moved to a job near Dolgellau. Having run away to get married to her, John lost his post at Ystumllyn but the two were clearly employable: living at Ynysgain Fawr they produced two sons and five daughters, but eventually moved back to work for the Wynnes at Ystumllyn. He died quite young, suffering from jaundice, aged 46. The pamphlet identifies the marriages of several of his daughters, who may well have descendants today. One son, named Richard, grew to adulthood and became Lord Newborough’s Huntsman at the Glynllifion estate. He is remembered as a ‘tall, calm man, who wore a Top Hat, Velvet Coat with a high white collar around his throat’. He had a family and lived to the age of 92.