by The Curious Scribbler

The professional geologists who joined Dr Tim Palmer for his tour of the building materials of the Old College last month were to be seen, pondering, with hand-lenses, on the grand stair which leads off from the entrance lobby on the landward side of the Old College. What, they debated, was the strangely uniform textured stone of which the cylindrical pillars are constructed? In a sedimentary rock geologists look for traces of fossils, (there were none), for bedding, which represents the layers in which the sediment was laid down, for variations in grain size of the rock. Part way up the stairs a pillar seemed to contain two largish clasts: lumps of material apparently contained within the stone, but insufficiently different from the matrix to resemble anything familiar to their experience. We knew, because it had been found in the archive, that Seddon used Ransome’s Artificial Stone in the building, but for which parts, the records did not reveal.

A prolonged online search through Building News, a weekly trade journal of the 19th century, has provided and illustrated the answer. In the issue for 14 April 1871 a short article reported that JP Seddon was to address the Institute of Architects the following Monday on the subject of the Old College and other buildings he had created in or near Aberystwyth ( Abermad and Victoria Terrace spring to mind).

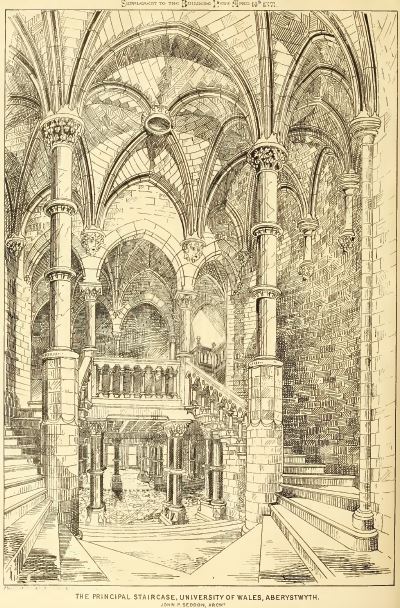

The Principal Staircase of the University College at Aberystwyth. Building News April 14 1871

The grand staircase is shown and the accompanying article reads ” The plan of the staircase, as may be sufficiently seen from our view of it, is complex. The first flight leading from the main corridor, which is curved, is a straight one. Then from the landing a few circular steps wind round each supporting column of the vaulting, and thence another straight flight on each side leads to the corridor on the first floor. The shafts of the columns are all of Ransome’s patent stone, and the capitals and vaulting are of Bath stone”. It was these shafts, and the eight-faced plinths beneath them, over which the geologists had been pondering.

Ransome’s Artificial Stone was quite a new product at the time the Old College ( then The Castle Hotel) was being constructed to the design of architect JP Seddon in 1865. It is described in an account of a meeting of the British Association of Science and Art in 1862. At this meeting Professor Ansted MA, FRS, read a paper on artificial stones describing terracotta, cements and siliceous stone, and the properties and disadvantages of each. Mr Ransome was present to stage a demonstration of his technique.

According to the account, sand, limestone or clay was mixed into a paste with liquid sodium silicate, which had been obtained by digesting flints in alkaline solution in an industrial pressure cooker. The paste could be pressed into a mould and then dipped into a solution of calcium chloride. Within a few minutes the pasty mass had hardened to stone and could be passed around the room. Large blocks weighing as much as two tons could be made by this method, and the material could already be seen in use in new facades of the Metropolitan railway in London.

Ransome’s patent stone was also used for making moulded shaped stones such as gravestones and grindstones for sharpening knives. It fell from use towards the end of the 19th century and Ransome’s son moved to America and became better known for concrete based materials and a patent horizontal rotary mixer.

Returning to the Old College, it seems there are other likely items of Ransome’s Artificial Stone, such as the distinctive stone fireplace hoods at either end of the Seddon room. Again lacking in any obvious geological structures, these uniform textured stones interlock with one another and were moulded rather that tooled by a stonemason into their complementary shapes. Utilizing different colours of sand in the mix allowed the production of alternate dark and light shades in the fireplace arch. The ornamental columns on either side are of real stone, Lizard serpentine, from Cornwall.

Fireplace hood, believed to be of Ransome’s Artificial Stone, in the Seddon Room

The odd looking clasts noted by the geologists inspecting stones in the staircase are now understandable, being consistent with their origin as distinct lumps within an imperfectly mixed paste rather than formed by a process of natural deposition.

The last word in this blog should go to the The Building News of April 14 1871, at which time the newly formed University College was soon to open in their recently acquired and unfinished building.

” We trust that the Committee will resolve upon finishing the work in the same spirit as that in which it was begun, and not spoil it by injudicious economy; for having purchased it for so much less than it cost, as they have done, a certain moral responsibility is attached to the bargain.”

I am not sure that “moral reponsibility” is a useful phrase to use in the current lottery bid to restore and revive this innovative building, but the intervening years have certainly seen underfunding, and the definitely injudicious application of thick layers of paint to some of the Ransome’s stone columns.

Pingback: A Tour of Old College | Letter from Aberystwyth