by The Curious Scribbler

Among the papers belonging to Elisabeth Inglis Jones is the draft manuscript of a talk she was putting together in later years which reflects upon her career as a writer of novels, biographies and articles. It includes reference to her last book on Augustus Smith of Tresco Abbey, so must have been delivered after 1969, when Miss Inglis jones would have attained seventy years of age. It commences with an account of her first novel, set in her native Wales, and the bruising experience that it set in train.

It is best recorded in her own words. “In April 1929, Starved Fields came out, nicely bound in grey with green lettering. But my joy and delight at seeing it in print was quickly obliterated by the storm which broke over my unhappy head. The widely read South Wales newspaper, The Western Mail immediately launched a full page scarifying attack on the book and its author. This did not gratify my parents who until then had been somewhat elated by my achievement. Then when a favourable review appeared in our local paper it only served to spark off a spate of indignant letters – a correspondence which went on in print for some weeks, and was very embarrassing. Worse still everybody began pinning names to my characters and one irate lady, an old family friend, wrote furiously to my mother saying the kindest thing to think of me was that I was suffering from a diseased mind.

Then suddenly the gales of wrath abated thanks to a certain Mr Herbert Vaughan, a very erudite man and the author of several books, who was related to a great many of our neighbours. His tastes were wholly dissimilar to those of his Cardiganshire cousins who held him in great respect. He had been much amused by Starved Fields and wrote me a very kind and encouraging letter, besides broadcasting his praise of it to all and sundry. Coming from such a literary authority as he was, his relations had to pipe down and we were soon on good terms again…”

Herbert Vaughan had himself published, three years earlier The South Wales Squires (Methuen 1926) an anecdotal history which had also been ill received locally because of the eccentricities he revealed. However he was of consequence in the region and had held the honour of High Sheriff of Cardiganshire in 1916, so his dismissal of the Western Mail’s as ‘spiteful and misleading’ will indeed have carried some weight.

It led me to spend a fruitful afternoon winding through microfilms of the Western Mail in the National Library of Wales in search of this offended and offending review.

The reviewer was Frederick J Mathias and the piece is entitled: A new writer on a Queer Wales. His first priority was to identify the new novelist – “Miss Elizabeth Inglis Jones …. Her story mainly concerns two unkempt Cardiganshire mansions and their derelict and generally disgusting inhabitants.” It is significant that Elizabeth and her publisher had not sought to make her gender obvious, for in the book her byline is E. Inglis Jones. Initials, or an ambiguous cognomen were a common stratagem by which women authors sought to receive a more serious hearing. At a similar time Somerville and Ross ( Experiences of an Irish RM) built a loyal readership of many years before they revealed themselves to be women.

So the odium of writing about flawed Welsh characters is compounded by the revealed identity of the author, and the Western Mail, untypically for a book review, included a head shot of Miss Inglis Jones to press the matter home. After a series of quotations from the book, Mathias concluded “In short in this book Welsh people are not allowed to speak or eat or look or live like ordinary persons. One poor man was even short because he was only five foot nine: surely the tall men must be giants in Tregaron. The story begins in 1896 and yet its barbarism suggests a prehistoric age. This is a pity because with her clever pen Miss Inglis Jones might have created a precedent by doing justice to Wales, instead of providing a sensation for the amusement of her English friends.” In a final flourish the enraged Mathias declared “The Tragedy of Wales is that Thomas Hardy was not a Welshman”.

It is difficult not to picture Frederick Mathias as a short, angry, racist Welshman. He even objected in his synopsis of plot that “The only real gentlemen who appear in the book are Englishmen”. Which is unnecessarily huffy since Inglis Jones’ Englishmen may be politely spoken, and tall, but they are unexciting and spineless creatures who get discarded by the women they court.

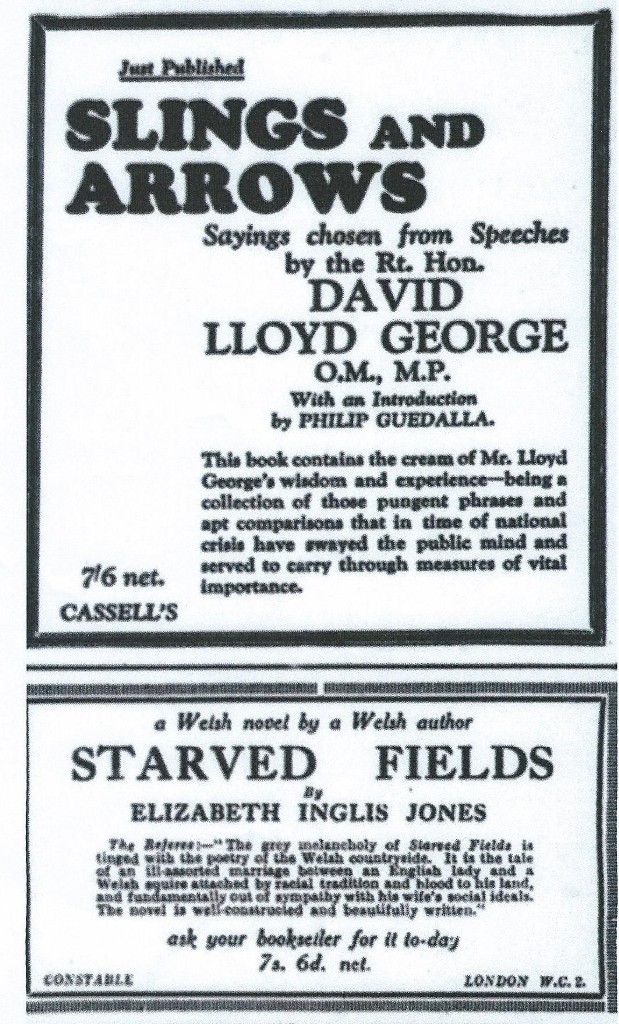

The publishers, Constable, responded by placing a large advertisement amongst the following week’s book reviews – A Welsh novel by Welsh author – and an extract from a favourable review.

The publishers, Constable placed an advertisement in 18th April 1929 with a view to countering the damning review in the previous week’s paper.

This advertisement also throws light upon the confusing question of Miss Inglis Jones’ given name. Was she Elizabeth with a z or Elisabeth with an s? Readers of Peacocks in Paradise, who are the most numerous of her present-day fans, will know her with an s. But inspection of her early titles shows that in her first few novels, Starved Fields (1929), Crumbling Pageant (1932) and Pay thy Pleasure (1939) she was Elizabeth with a z. And her supporters and critics in 1929 addressed letters to her as Elizabeth. It seems that not long after moving permanently to London, she adopted the more distinctive spelling by which she is now generally known.

( Elizabeth Inglis Jones’ debut novel is described in the preceding blog)