by The Curious Scribbler

The guest of honour at the recent opening of Mrs Johnes’ garden at Hafod was new supporter, Giles Inglis Jones, a great nephew of the author Elizabeth Inglis Jones, whose account of Hafod did so much to resurrect the memory of Thomas Johnes when Hafod was at its nadir of destruction.

Giles Inglis Jones, assisted by his daughter, reads an extract from Richard Payne Knight’s poem The Landscape a didactic poem (1794) in praise of the Picturesque to the guests of the Hafod Trust.

Inglis Jones’ book, Peacocks in Paradise, published by Faber in 1950, was a fictionalised biography of the Johnes family which drew heavily upon the large collection of personal letters between Johnes and his friend Sir James Edward Smith which she discovered at the Linnean Society. These letters have been among the most valued resources for subsequent historians and some are reproduced in Richard Moore Colyer’s A Land of Pure Delight ( Gomer 1992).

Miss Inglis Jones was approaching fifty when she turned her hand to this, the first of her biographies, and later went on to write well researched accounts of the lives of other notables, Maria Edgeworth (1959) and Augustus Smith of Tresco Abbey in the Scilly Isles (1969). However her debut novel in 1929 was far steamier fiction, which roused in equal parts the admiration and the indignation of the readers of Cardiganshire. I have just finished reading Starved Fields with very considerable enjoyment and even a little surprise that such insight and earthy sentiments should flow from the pen of an innocent young woman of good family.

Starved Fields deals with the families of two Cardiganshire Squires, the baronet Sir Uryan Williams, squire of the crumbling eighteenth century mansion Bryn, and farming landowner Owen Morgan of Lluest his relative and neighbour. Just as one cannot read Wuthering Heights without realising that the author had a close understanding of alcoholism, depression and mental illness, it is hard to believe that Inglis Jones’ pageant of male and female drunkenness, incompatible marriage, illegitimacy and adultery was not informed by close observation of her neighbours or even family.

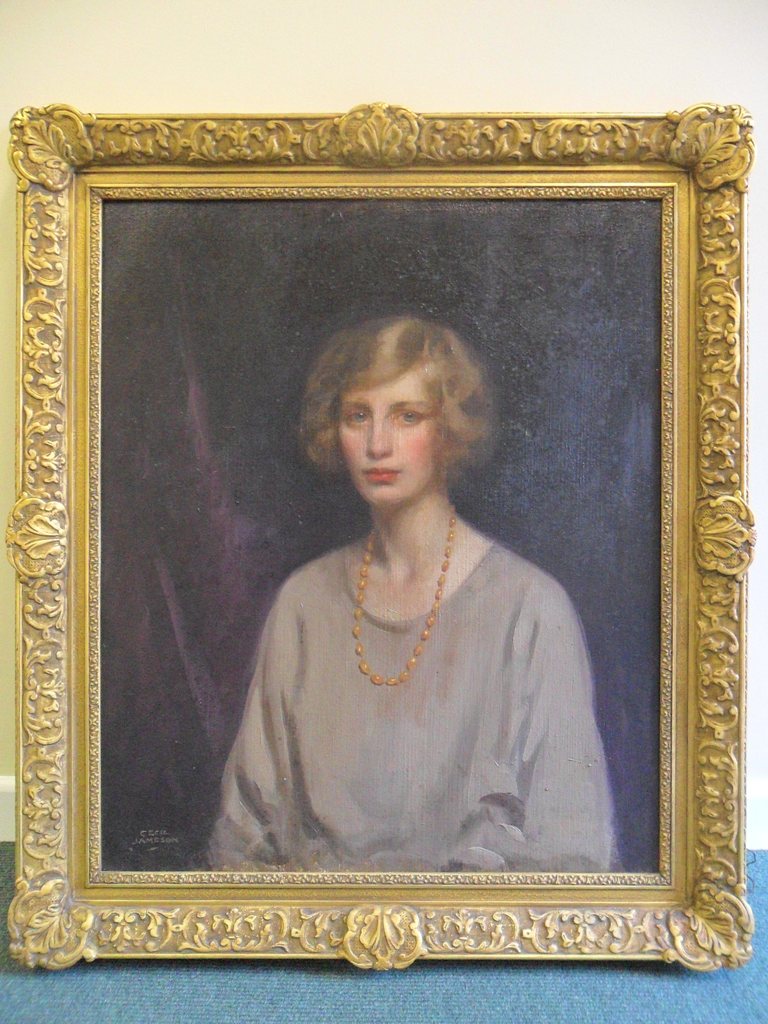

Giles Inglis Jones has loaned to the Hafod Trust an oil painting of his great aunt as a young woman, painted by the New Zealand portrait artist Cecil Jameson. She is a pretty girl with a short 1920’s bob of hair, wearing a simple shift and a necklace of amber beads. She was brought up at the south Cardiganshire mansion of Derry Ormond though I have heard it said that she and her brother considered their childhood deeply unhappy and shed few tears at the eventual demolition of their family home.

The men she depicts in her first novel tend to be spineless, inconsistent characters, at best charming but wet, and at worst drunken and entirely selfish. Perhaps that is why she never married. The strands of her story all paint entirely believable characters, but only one for whom the author shows real compassion. This is her heroine, Gaynor, daughter of the baronet, who ends up balancing the role of adulterous mistress and farm manager to her feckless first love, Owen Morgan, with that of dutiful daughter to her enfeebled and alcoholic parents.

Also loaned from Giles Inglis Jones’ deceased great aunt’s possessions came a number of deeds and notebooks some of which I have been perusing. One contains a transcription of 21 letter received in 1929 as a result of the publication of Starved Fields. While all the writers congratulated her on her work, readers struggled with such depravity set in the Cardiganshire of the 1890s. The Principal of St David’s, Lampeter, Canon Maurice Jones wrote “Where you have gone wrong, if I may venture to say so, is in setting your period a century late. I cannot believe that the life you describe is true of Cardiganshire only 30 years ago, whereas the book gives a fairly clear and honest description of life in many parts of Wales in the 18th Century …. I’m afraid you will not be popular with the “county” after your remorseless revelations of what life can have been like in Cardiganshire at any period in its history”. Mrs Perrin ( author of 21 novels ) declared “What you must cultivate if you want a wide public is more restraint – your construction and technique are good but remember too much realism isn’t art”.

Miss Mary Lewis of Trefilan tempered her congratulations with a rebuke “Now there are aspects of Starved Fields I don’t like my dear Elizabeth, but I’m not going to enlarge on what is a matter of taste except to say that Society in Cardiganshire during the Nineties wasn’t really at all what your book implies – You weren’t born then, but I was (unfortunately) grown up and going about in those days so I know” . The Spectator’s reviewer took the view that the novel could only have been written by a man.

On the basis of these letters, it seems that actually the gentry were less offended than the middle classes. A letter from her cousin, Wilmot Vaughan of Trawscoed states “I do think you have got the Welsh country people to a T, let alone strange, weird drunken squires who one has known in the flesh.”

Lady Lloyd of Bronwydd was simply thrilled. “ What an amazing child you are! I must congratulate you on your wonderful book, not a nice character in it!! But your perspectives are quite an astonishment and it is terribly true and interesting and I own to simply screaming over it until Marteine got quite angry, but he couldn’t put it down!! “ More prosaically she added “ I expect your mother is very proud of you, I should be. Will you dare go back to Derry [Ormond]?”

I don’t know whether Elizabeth did return home, but certainly by 1937 she was a permanent resident in London. I believe that the remoteness of their homes and the relative poverty of even the premier families in Cardiganshire made it very difficult for many gentry girls from West Wales to secure suitable husbands. Elisabeth certainly made her escape into London and literature, and by her middle years had started mining the historic record rather than her own life for what are now her better known books.

Her pretty portrait will soon be presiding over new nuptials in the Hafod Estate Office which is now a venue for civil marriage ceremonies. Inoffensive young woman that she appears, her clear gaze should make brides closely inspect their motives, and keep new husbands on the straight and narrow!