By The Curious Scribbler

During the ennui of lockdown I have been researching a little piece of Ceredigion’s black history.

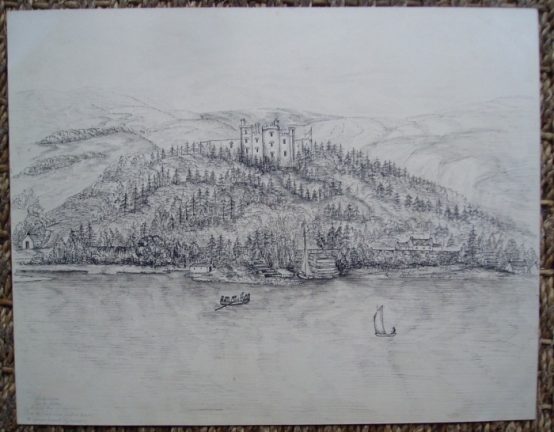

My subject was Justina Jeffreys of Glandyfi castle, that eccentric Regency Gothic castle which perches above the (now straightened) Glandyfi Bends on the way to Machynlleth. It was built in 1818 as the fashionable designer home of Shrewsbury born lawyer George Jeffreys and his new bride Justina Scott. Justina had grown up at Bodtalog, a small country house near Tywyn, as the child of the bookish intellectual Edward Scott and his wife, the widow Louisa de Saumaise. It has long been believed that she was the model for Anthelia the heroine of Thomas Love Peacock’s first novel Melincourt. Anthelia is described as a highly rational young woman brought up and educated in solitude by a man of ‘great acquirements and of a retiring disposition’.

Glandyfi castle sketched by Francis Wood in 1838

But all was not as it seems, for Justina was not born a Scott. She was born in Jamaica in 1787 the daughter of the premier army man then posted to the island, Captain Charles McMurdo of the 3rd East Kent Regiment “the Buffs” and a young woman called Susan Leslie. In the eighteenth century colonies bastardy was a very common phenomenon, on most pages of the parish birth records the children born in wedlock are the exception rather than the rule. I cannot believe that the church actively approved of this situation but its clergy were diligent in recording the facts. Fathers are normally named, and race and status was a matter of record.

So we know that Susan Leslie was a free mulatto, who underwent baptism in the Anglican church at the same time as her new daughter. A mulatto is a specific term, it means she had one black parent, and given the social structure of the slave economy it is highly likely that that black parent was a woman and a slave.

Justina’s conception was more than a one night stand, for two years later her brother was born, also sired by Captain McMurdo, and named Charles McMurdo.

There might have been more illegitimate McMurdos were it not for the fact that Captain McMurdo’s posting in Jamaica came to an end, and he was sent off to Canada, where he eventually married a well connected young woman from a loyalist family, named Isabella Coffin and started a second family. His first legitimate son was named Charles Alured McMurdo (the unusual second name being a nod to the Governor of Jamaica, Alured Clarke under whom McMurdo had served).

Susan Leslie remained in Jamaica, and must, I believe, have been a handsome and sought-after young woman. She was soon the partner of a Scottish doctor, John Wright by whom she had two more sons. She was, or in her lifetime became, a woman of property for her will, written on a visit to London in 1801, distributes her land, buildings and slaves among her three sons, and names both the fathers as executors of the will.

It is touching that in the will she leaves to Justina her ‘apparel, trinkets and her silver spoons’. In a subsequent codicil she rescinds these small gifts because her daughter has been amply provided for by McMurdo. So how had McMurdo provided?

Justina had been removed from her mother and ‘adopted’ by Edward Scott, who during the Jamaica years had been Captain McMurdo’s junior officer, First Lieutenant in the same regiment. Edward, an impecunious younger son of an aristocratic Kent family had no children of his own, but when Justina was just three years old he had married, possibly for money, the wealthy widow Louisa, who happened to be the widow of his first cousin Count Louis de Saumaise. It was through Louisa, daughter of welshman Lewis Anwyl, that he winded up living comfortably as the squire of Bodtalog with Louisa and Justina. I would speculate that when Justina was five or six years old she was shipped off to her new ‘uncle’. She must have been quite young to have been so well educated and nurtured as a Welsh gentlewoman, but not so young that her brother Charles did not remember her. While there is no evidence that the siblings met again, by the age of 20 Justina’s brother Charles McMurdo was in Limehouse, London founding a family of several generations of boat builders. He and his descendants repeatedly named their daughters Justina.

Although Justina is named as Justina Scott in the marriage register her paternity was no secret, it was known to the Jeffreys family into which she married, and her birthplace, Jamaica, is recorded in the census. Her high-status white father, McMurdo, would have been a matter of pride rather than shame, just as Mary Seacole, who we now venerate for her blackness, was openly proud of her Scottish military father. Justina’s story reminds me of other examples of the rapid social mobility of the mixed race offspring English and Welsh gentlemen in the eighteenth century. The purchaser in 1803 of the Piercefield estate near Chepstow, for example, was Nathaniel Wells the Jamaican-born natural son of William Wells, his offspring by a house slave known as Juggy. Nathaniel’s origins did not hold him back, he became the high sheriff of Monmouthshire.

George and Justina seem to have enjoyed a nice life in their pretty castle, and produced eight children all baptised at Eglwysfach church, where her old admirer Thomas Love Peacock also showed up to marry Jane Gryffydh in 1820. Justina’s relationship with her adoptive parents also seems to have been good, two of her children bear the names Edward and Louisa, and when the very elderly Edward Scott eventually died aged 90 his estate, barring various legacies, was placed in trust for Justina for her lifetime.

Glandyfi castle first went on the market in 1906 when it was sold by two of Justina’s granddaughters. Several lines of descent from George and Justina have been extinguished in later generations, but some persist in New Zealand and America, and have been known to turn up on holiday to visit the castle. Today it is for sale once more for £2.85million.

Glandfi Castle sale particulars in Country Life 2020

The full story of my researches have been accepted for publication in Ceredigion, the Journal of the Ceredigion Historical Society and will appear in 2022.