by the Curious Scribbler

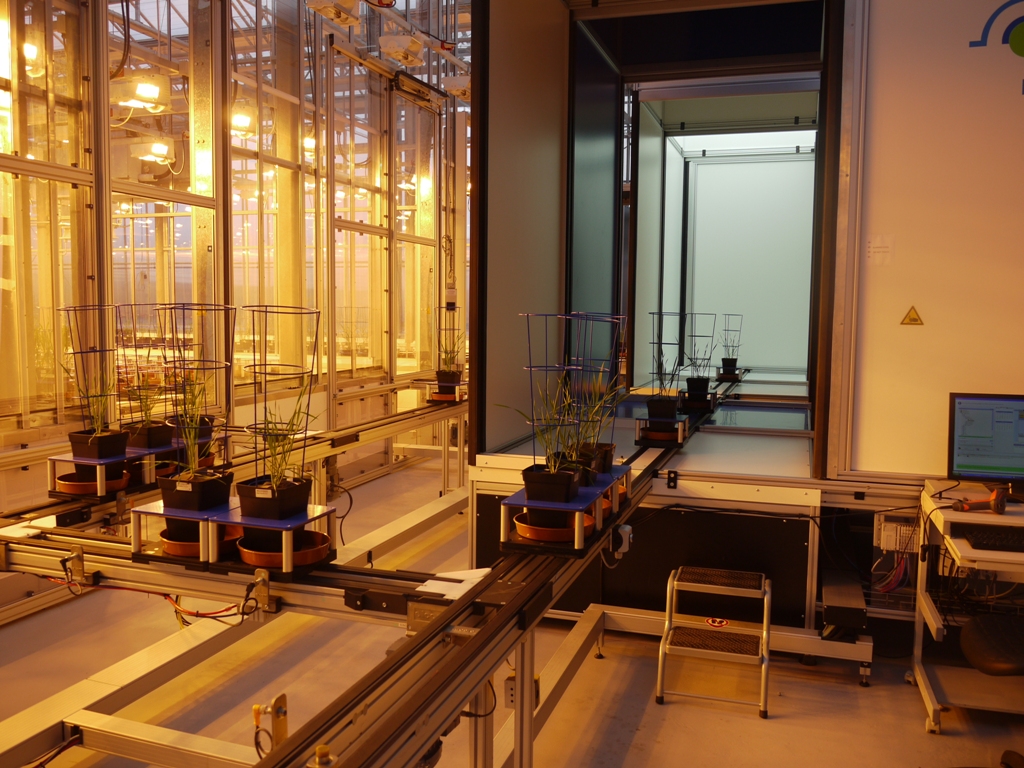

The long dark January has given me plenty of time to peruse one of last year’s purchases, that hefty doorstep of a book ” The Families of Gogerddan in Cardiganshire and Aberglasney in Carmarthenshire“. It was launched last March at the National Library of Wales by its author, Sir David T R Lewis,and I handed over my £30 with enthusiasm for it is a subject of which I was eager to learn more.

Sir David Lewis is of Carmarthenshire farming stock whose elevation to the knightage in 2009 follows a glittering career in the law and a stint as Lord Mayor of the City of London in 2007. Taken together in this book he has assembled a large body of information and a lot of pictures about an interesting family and their homes.

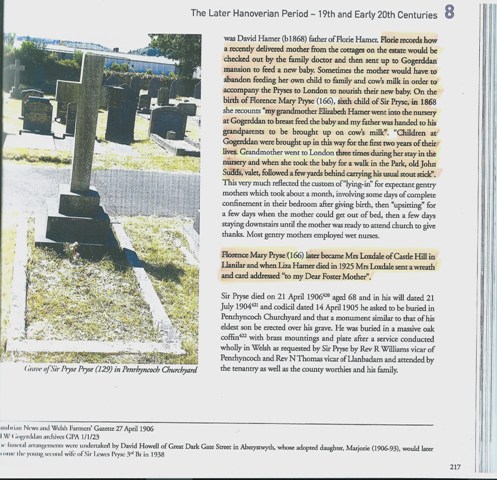

The book, however, proved to be packed with surprises, the first of which was to find material from one of my blogs extensively reproduced without attribution on p217. In my Letter from Aberystwyth of 7 October 2015 I wrote about Florrie Hamer, whose grandmother had acted as wet nurse to Sir Pryse Pryse’ wife in 1869. It is funny how one can suddenly recognize one’s own words amongst those of another author. When I got out the highlighter pen I found a remarkable similarity!

His book – my text!

In 2013 I devoted a blog to the interpretation of the Anno Mundi dates upon the gate posts of Bwlchbychan and and the stables at Alltyrodin. Perhaps we were working in parallel, but the account on p201 strongly suggests my blog was his (unacknowledged) source.

I am not the only historian to have noticed an uncanny resemblance to their own work. It is ironic that the author’s copyright statement at the beginning of his book reads ‘permission is granted to quote inextensively and without photographs from the contents of this book provided attribution is made to the author with an appropriate footnote or source note’.

Soon I happened upon a splendid howler: a panel about Nanteos on p 267 revealed that the eccentric George EJ Powell was ” Etonian, scholar and friend of Byron, Swinburne, Longfellow, Rossetti and Wagner“. Powell, who lived from 1842-1882 certainly hung out with Swinburne, and he corresponded with Longfellow in seeking approval for his early poetry, but Byron! Byron died eighteen years before George was born, so this is clearly impossible. I can only think that Sir David has been influenced by the recently-placed creative name plates on the doors of Nanteos mansion in its present incarnation as a hotel. They do have a Byron room, and a Marquis de Sade room, but this is not a good historical source for nineteenth century history.

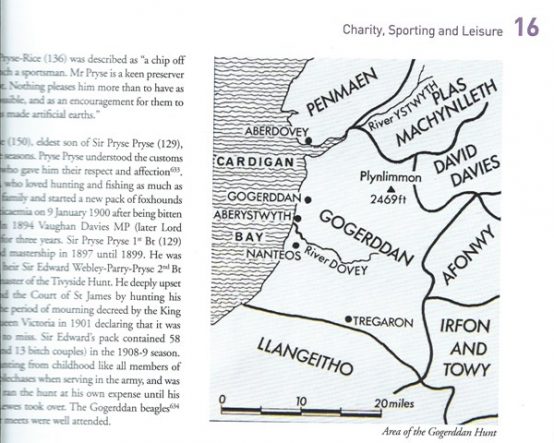

The I came across a map in which the Dovey is labelled as reaching the sea at Aberystwyth and the Ystwyth at Aberdovey.

Lewis has assembled a large amount of information, some of it his own, and illustrated it lavishly with contemporary and historic photographs. Many I recognize from the collections of the National Library of Wales, while others are new to me, and sourced from private individuals who have shared their property and are properly identified below the picture. What is surprising is that the photos held in the National Library are rarely identified as such, and in many cases the quality of reproduction suggest they have been photocopied and reproduced from earlier publications, in which the source was properly acknowledged. Such a shortcut presumably avoids the NLW reproduction fees.

Such failings of scholarly etiquette would not be surprising in a school project, but seem very cavalier on the part of an Honorary Fellow of Jesus College, Oxford, and a Member of Council of at least three Universities. His publisher might be feeling rather embarrassed .. but then, he is his own publisher.