by The Curious Scribbler

Plants, mainly grasses, have been being selected and improved at Aberystwyth for almost a hundred years. Modern experimental oat breeding, for example, began here in 1919 along with experiments designed to improve the properties of forage grasses for sheep and cattle. In those bygone days the research organisation was called the Welsh Plant Breeding Station (WPBS) and it was directed from 1919 to1942 by George Stapledon, who was duly knighted for his endeavours towards achieving what we now call ‘Sustainability and Food Security’. In those days it was called ‘Autarky’. In the Seventies we called it ‘Self-Sufficiency’. (In any case, all these terms mean producing more, with less dependence on imports and political alliances).

I recently saw some charming photos of the early days of plant breeding at Aberystwyth. Airy greenhouses contained bevies of women in pretty dresses, meticulously stripping the male parts (the anthers) from oats or other grasses and pollinating the stigmas with paintbrushes loaded with the chosen pollen. Over the years the Welsh Plant Breeding Station grew in size and importance, moving in 1953 to the Gogerddan estate, of one of the former great mansions of Ceredigion, at Penrhyncoch. The Queen came to open the new establishment. The former walled garden of the estate soon disappeared under a complex of modern buildings.

In the 1990s after various mergers WPBS renamed itself the Institute of Grassland and Environmental Research (IGER) and then to the bewilderment of many, mutated once more, by merger with Rural and Biological Sciences at Aberystwyth University into IBERS (The Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences). Many still know it by its older acronymns, especially the large local workforce who since its inception found employment in its glasshouses, fields and experimental plots. Today IGER oats account for 65% of the oats planted in Britain and IGER varieties of rye-grass are contentedly masticated all over the world. IGER turf has been developed for the particular needs of different sporting venues, and even to grow on vertical surfaces to enrobe green sculptures.

Meanwhile the sophistication of genetic engineering moved on from the days of girls in pretty dresses and now involves the scrutiny not just of new hybrids but of individual genes. And to mark the twenty-first century IBERS has a startling new toy, The National Plant Phenomics Centre, one of the most advanced experimental greenhouses in the world.

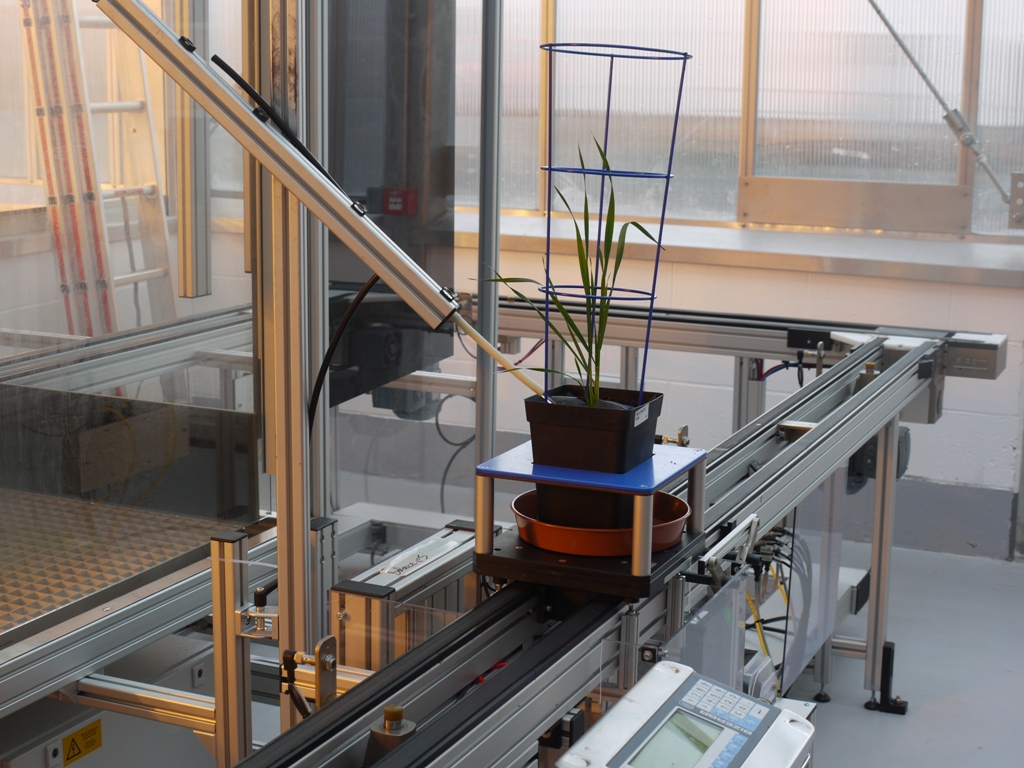

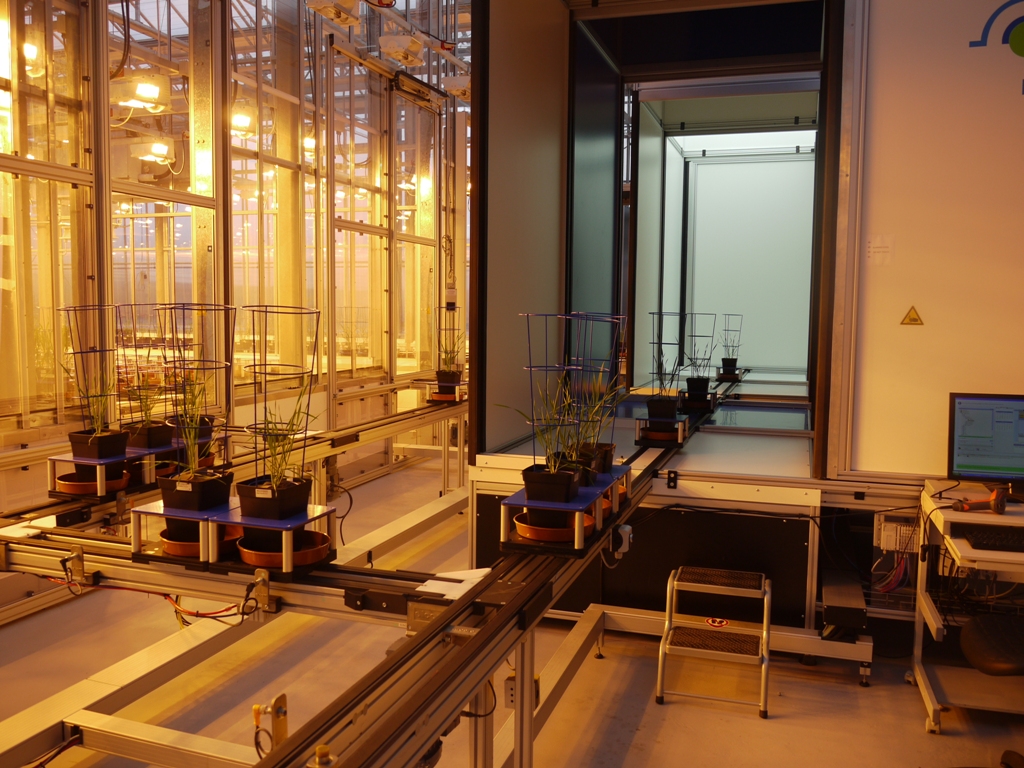

In the National Plant Phenomics Centre glasshouse, plants leave the artificial sunlight for a visit to the measuring chambers.

Here in a giant brightly lit glasshouse, plants reside in identical individual pots, moving gently around the huge space on whirring, clicking conveyor belts. Each pot contains a microchip which identifies its programmed needs. Each plant may have been designated for a personalised regime of water, fertiliser, pesticide. And each plant is daily monitored. As its progresses along the conveyor belt it pauses, turns to the left and passes into a chamber like a lift, whereupon the automatic doors close it from view. Inside it is rotated and photographed from four sides and above so that a computer programme can compute its precise enlargement since yesterday’s visit to the chamber. In another chamber it may be lifted out of its pot to measure the root growth under infra red light, or measured for fluorescence. Then the doors open and the belt moves on. Then there is a breathless pause. The plant pot stands upon a scale by which its weight indicates the amount of water it has lost or used since last it visited this point. The pause continues, the computer deliberates, and then according to its needs and the experimental programme, a downward angled gun delivers a precisely measured bolt of water to the roots. There is a further click and the patient moves on, to be followed by another and then another. There is a remarkable sense of suspense in watching a series of identical plants passing the weigh station, some to be rewarded with a drink of water, others assessed, measured and sent on their way thirsty.

The multi-million pound National Plant Phenomics Centre opened very recently. It is a magnificent piece of sci-fi, with all the man-appeal of a train set. Quietly clicking and whirring belts drive continual motion, not a human in sight. Watch the You Tube animation here.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qBsVP0j70k

It looks as if fewer local jobs will arise from the National Plant Phenomic Centre than from the old techniques of watering cans and trial plots, for it is all controlled by computer from a single work station. In the animation you will find that the sole operative of the laboratory computer terminal looks suspiciously like superheroine Lara Croft. The film is accompanied by a mind numbingly repetitive electronic music sound track. Only in this respect does the animation exceed reality.