by the Curious Scribbler

In November, when writing about Snowdrop marble, I planned to return to another beautiful and distinctive Welsh stone – Halkyn marble from the Carboniferous limestone of North Wales. I am grateful to Andrew Haycock of the Welsh Stone Forum for introducing me to this pretty stone.

Halkyn marble font in St Mary the Virgin Church , Halkyn.

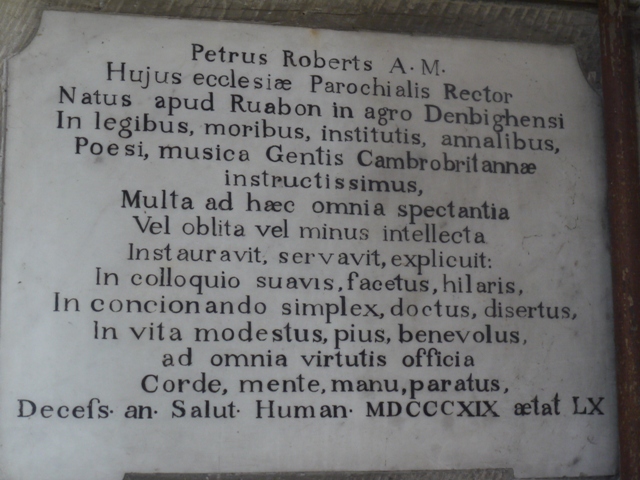

This stone was recognised for its ornamental potential in the early nineteenth century, when the Marble quarry first appears in the will of John Salisbury in 1837. It qualities are amply displayed at Halkyn church, a spectacularly lavish Victorian church built by the First Duke of Westminster in 1877. At that time the Duke was employing Chester architect John Douglas to extend Halkyn Castle in the Elizabethan style and, finding the existing parish church to be somewhat shabby and, worse still, interfering with the view from the castle, he demolished it entirely and built a new one, also by John Douglas, on a nearby site. As is often the case with such vanity projects, the unattractive old memorials of the former church were not transferred, except for a Latin-inscribed slab to a former rector, Peter Roberts and an unexplained but damaged alabaster effigy which hints at an important memorial now lost.

Peter Roberts, Rector, died 1819 must have been fun at dinner ! “In conversation suavis, facetus, hilaris” – suave, facetious and hilarious – or at the very least, ‘Sweet, witty and cheerful’

The master mason who built the new church out of local Gwespyr sandstone was also the owner of the marble quarry at Pant-y-Pwll Dwr, five miles away. He lost no opportunity to showcase its qualities in the church interior. Four handsome pillars of Halkyn marble separate the nave from the north aisle, the pulpit stands upon a plinth of the stone, and the barrier between nave and chancel is topped with this polished stone. Typically available in slabs up to 18 inches thick, the massive font is carved from three layers of this particularly impressive rock, with a stem of black marble, probably also of local origin.

Interior of St Mary the Virgin, Halkyn

Interior stonework in Halkyn Marble

The appeal of this stone comes from the fossils within the grey matrix. These are the stems of sea lilies – crinoids – which were an abundant form of sessile echinoderm, relatives of sea urchin and starfish. Cut across they look like beads, cut obliquely whole stems are visible. At a lesser frequency are large bivalved seashells, – productids – which generally look like curved C-shapes in section.

Pillar formed of blocks of Halkyn marble

Large slabs of Halkyn marble also went to the Duke of Westminster’s Victorian Eaton Hall which was a gothic turretted monstrosity built to a design by Alfred Waterhouse in the 1880s and demolished eighty years later.

Eaton Hall in 1907 a photograph by John Steggall Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1339190

Halkyn marble may well have found its way to other properties of the Grosvenor estate.

The original quarry is long gone, subsumed into a huge Cemex quarry just south of the A55 North Wales Expressway, where these abundant fossils are ground up to make road-stone. Adjoining the modern quarry one can still find smaller outcrops in which the crinoid stems are eroded by the weather to stand proud of the surface.

Halkyn marble weathers out to expose the crinoid stems

the disused quarry at Bryn Blewog, just across the road from Pant-y-Pwll Dwr the giant Cemtex quarry.

When dry and unpolished the stone just looks grey, raindrops expose some hint of its potential beauty. It is heartening to know that Gwyn Davies stonemason of nearby Rhes-y-cae was able to obtain 100 tons of quality beds of Halkyn marble from the Cemex quarry, so it is still possible to commission a fireplace or stone slabs to ornament a modern project, or to restore a historic one. A new piece was used in 2011 to mark the end at Chepstow, of the Wales Coast path.

Slab of unpolished Halkyn marble (left) and of Pennant Sandstone (right) mark the end of the Wales Coastal path at Chepstow. copyright BBC News in Pictures