by The Curious Scribbler

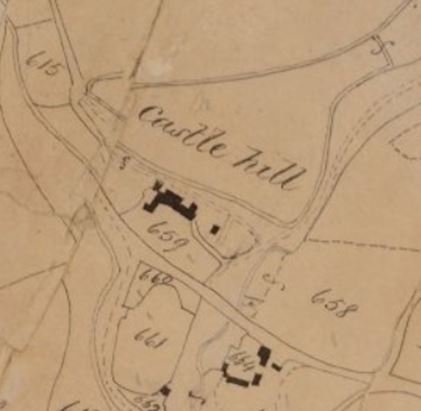

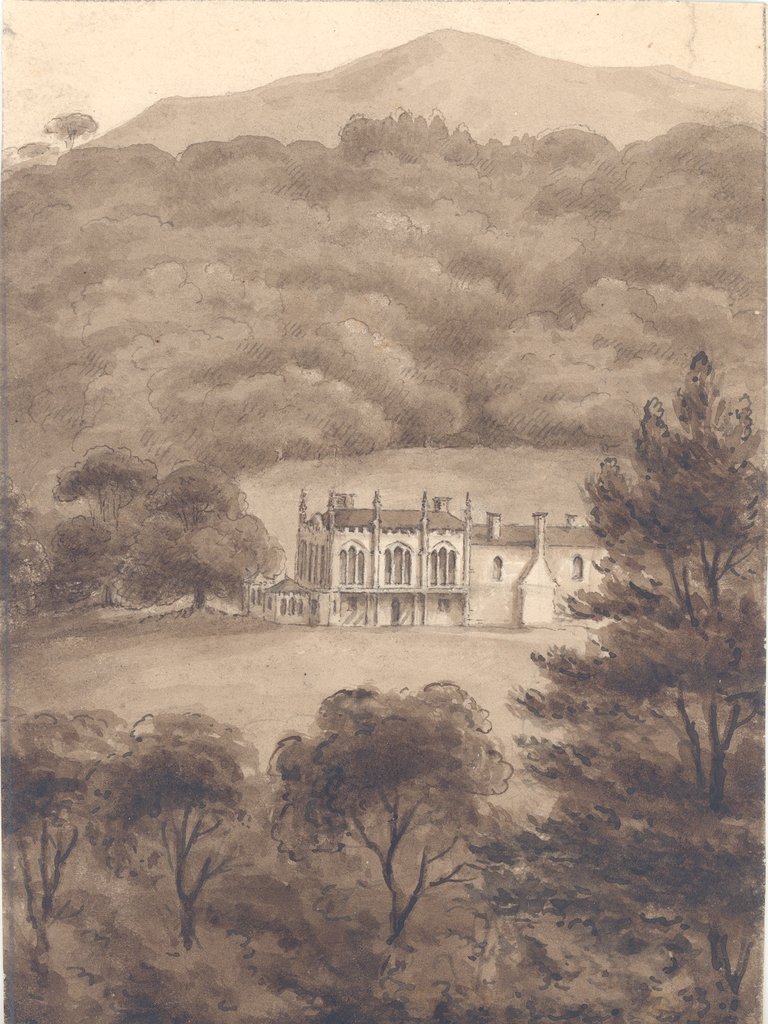

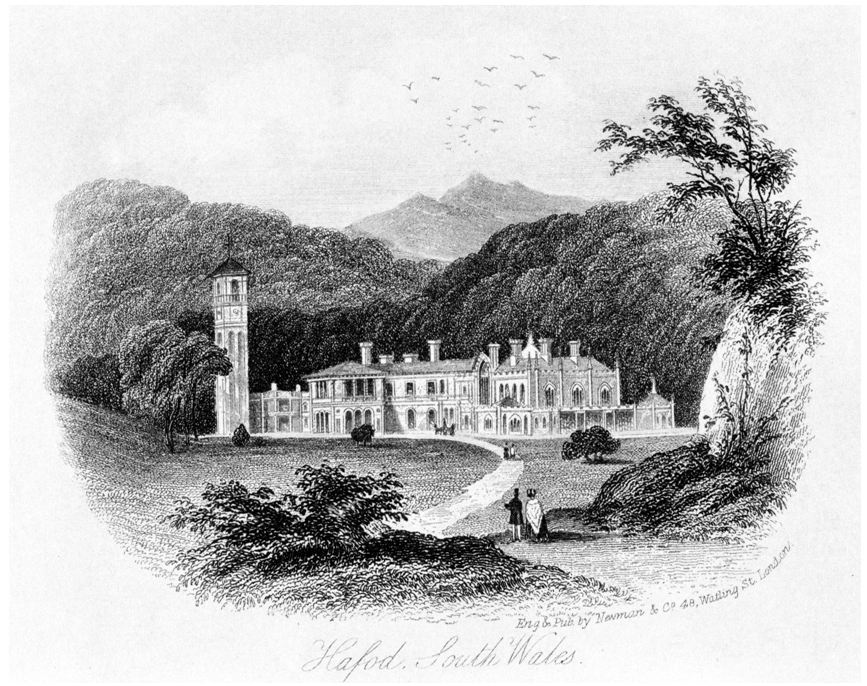

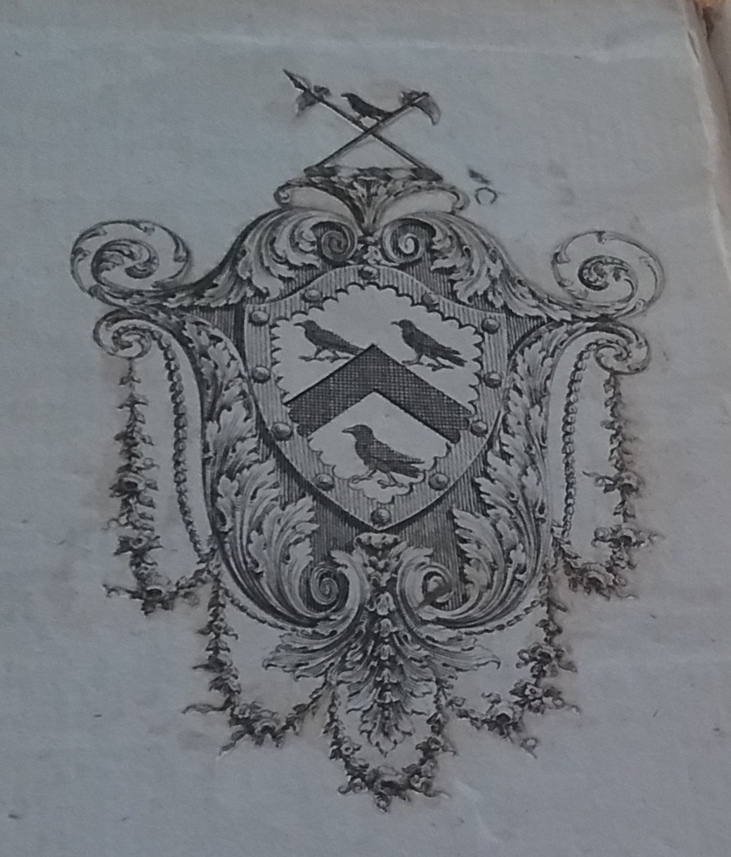

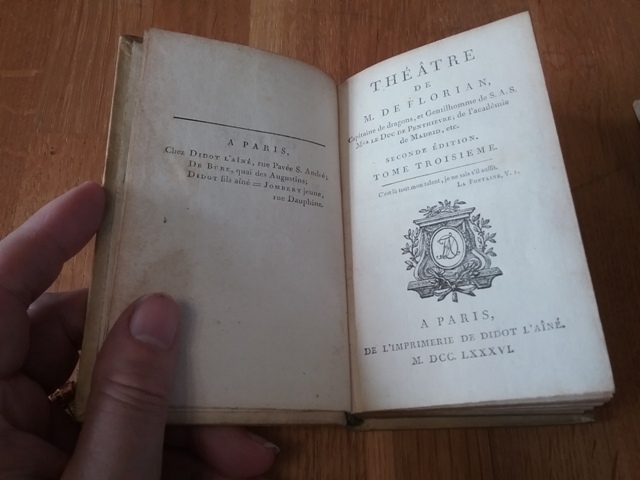

Hafod has an illustrious history of landscape artists. In 1798 J.W. Turner painted the original house glowing in sunshine beneath an exaggerated mountain wreathed in cloud. J. ‘Warwick’ Smith painted a series of views which were later published as handsome aquatints in A Tour to Hafod by J.E. Smith, in 1810. Many of these images are familiar to us as postcards – especially The Peiran Falls in spate, gushing either side of the central outcrop, the Cascade Cavern approached in those days by a three gentlefolk and a dog who have just crossed a long lost rustic bridge, the meadow with resting cows by the river. Rarer but equally choice are the elegant views baked onto Derby Porcelain to create the Hafod dinner service for Thomas Johnes in 1787.

Items from this service occasionally appear on the antiques market. The largest collection of about twenty pieces is on display at the the national Museum in Cardiff.

A plate from the Hafod service

The following centuries have seen many further artists’ contributions, ranging through talented 19th century tourists and at perhaps the lowest point in its history, the 20th century artist John Piper. His scratchy impressionistic views of the Ystwyth Gorge gave The Hafod Trust the only clear basis on which to reconstruct the dilapidated pillars of the Gothic Arcade above the river.

In the last five years two new artists have been annually introduced to Hafod courtesy of a residency offered through the Royal Drawing School. The successful applicants, all graduates of the School, live for two weeks in the holiday cottage Pwll Pendre, and explore, paint and draw on the estate. This afternoon I went to meet this year’s two artists Yiwei Xu and Iona Roberts at an exhibition of their work in their temporary studio in the Hafod Stables. Tacked to the wall were paintings and sketches inspired at Hafod, some finished, others to be worked up into finished pieces when they return home. Both had perspectives on some of the same views.

Yiwei Xu ( left) and Iona Roberts ( right) Artists in residence at Hafod 2023

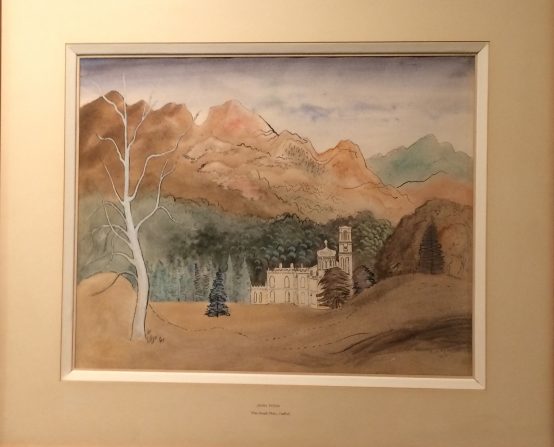

Yiwei was deeply impressed with the beauty and wilderness of Hafod and concentrated colorfully on the busy matrices of branches and tree trunks and rock. She told me she had never previously been so far from the urban experience. She had painted in London parks but was greatly delighted with the lone Sequiodendron gigantea which stands near the walled kitchen garden, placing it centrally in one of her larger pictures. Another view showed the Gothic Arcade perched above the gorge.

Yiwei Zu’s picture wall

Three of Yiwei Xu colourful views of Hafod

The Sequoidendron appeared in Iona’s pictures too, with the mountains delicately delineated behind. The Gothic Arcade also loomed indistinctly amongst dappled black and white foliage further dappled by actual raindrops falling on the paper while she worked. Intricate fine brushwork characterized many of her sketches and I was particularly taken with two black and white views taken from the bastion on the drive which overlooks the Ystwyth and lead the eye upward to the bald mountain to the east. She had also done colourful oil paintings of Hafod church and Pwll Pendre cottage in a busy landcape. Iona currently teaches at the Glasgow School of Art, and will be doing another residency in the autumn at Dumfries House in Ayrshire.

Ioan Roberts’ picture wall

Two views up the Ystwyth at Hafod by Iona Roberts

The residency was begun six years ago by the Hafod Trust. The new guardians of Hafod, the National Trust, intend to continue the tradition and it is hoped that in due course an exhibition of contemporary artists’ work on Hafod will be put together, and the Royal Drawing School artists will be among the exhibitors.