Last Saturday was not a day many people willingly ventured out. It was the third of three days on which a blisteringly cold wind from the Russian steppes seared its way across Ceredigion, and although unlike north and east Wales we had no snow, the chill factor made the eyes water and the marrow shrink. Setting out from our home we soon encountered our first obstacle a massive ash tree, fallen and pivoted on the hedge bank to block the road. When leafless trees fall it is a high wind indeed.

Notwithstanding this, a small group of specialists converged from all over Wales to explore the building stones of south Ceredigion. Our topic for the day was a locally occurring Ordovician sandstone, one form of which, Pwntan stone, has already been mentioned in this blog, as the stone from which Tremain Church is built.

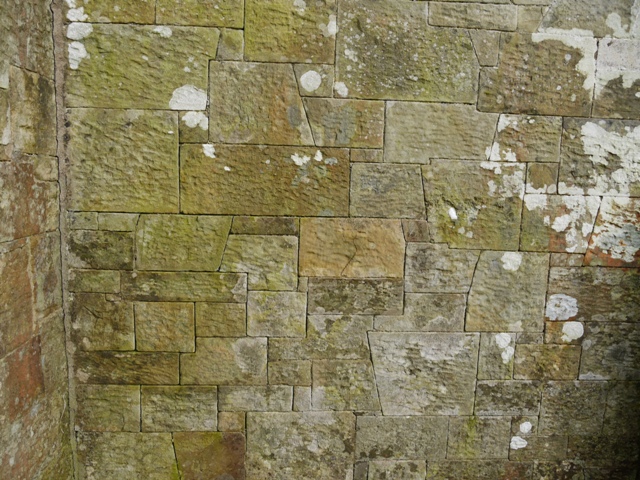

First we met at Tan y Groes. Here the main road is constricted by sandstone buildings on either side of the road, and speeding traffic roars through the gap. There is a Calvinistic Methodist chapel on the south side of the road with adjoining vestry building. Recently modified for residential use, the gable end facade has been recently cleaned by sandblasting. So many different styles of ornamental tooling can be seen. The main construction blocks have been pecked and pock marked with many short chisel blows. The edges of narrow ornamental dressings are transversely grooved, across the shorter axis of each stone. The voussoirs of the window arches are similarly ornamented and where large stone are used, a false division has been carved, to create the appearance of two or even three smaller voussoirs instead of a single block. The building was commenced in 1849 a year after the completion of nearby Tremain. It is not known whether it is by the same mason, but it is certainly work by a meticulous craftsman. The characteristic interlocking stones of Tremain are not here however. Perhaps Calvinism is better represented by uncompromisingly coursed blocks. Other buildings in the village are yet plainer, built of rubbly blocks of sandstone. The chapel buildings could only have been created with hand-sawn stone.

St Michael’s Tremain has already been described. It is the perfect habitat for the creamy white crustose lichen Ochrolechia parella. On the west end the lichen is so extensive that the building is almost white. The toxicity of lead to lichens is nicely illustrated by the two strips of stonework below the lancet windows. When rain drives against the leaded windows and runs down to trickle off the sill it poisons the lichens and the stonework remains clean.

No such problems exist for the lichens in the churchyard at St Michael’s Penbryn. Here is a charming long low whitewashed church set in a circular graveyard on a hill above the sea. Here many of the 18th century stones are completely white with lichen, but remarkably the inscriptions can still be discerned because the lichen follows the carved indentations beneath. The stones have a characteristic shape curved at the top with square shoulders beneath. There are several grander graves in which the same round topped, shouldered shape is formed in cut blocks of pwntan stone framing an inscribed slab of slate or sandstone. They date from 1780-1820 and stand like theatrical doorways on the sloping plot. At first sight you might think them whitewashed, so extensive is the lichen cover.

One of about 30 small gravestone at St Michael’s Church Penbryn. carved Pwntan stone is a perfect substrate for the lichen Ochrolechia parella

St Michael’s Church, Penbryn is a medieval church, with later restoration. Characteristic round topped, shouldered gravestones date from the late 18th century

There are various places east of the main A487 where sandstone was formerly extracted but most are long neglected and overgrown. The group then went on to visit Gwarallt quarry, Bwlchyfadfa near Talgarreg where farmer Iwan Evans has had the initiative to re-open the quarry which supplied high quality sandstone in the 19th century. In a trade magazine of the 1880s it was vaunted as stronger, and cheaper, than Portland stone. The stables at nearby Alltyrodin mansion were certainly built from Gwarallt stone, but whether it was exported over a larger area is lost to history.

In the quarry one can see the thick beds of sandstone dipping down at 45° to the field above. Big blocky stones are quarried from the face and can be cut for paving slabs or shaped for modern stone building or restoration work. Some beds are too thick, yielding several-ton chunks too large for the saws on site. There are some monstrous blocks waiting by the road to catch the eye of a sculptor. Pwntan stone holds the sharp detail of its carving for hundreds of years. It would be a good choice for a new work of art.

Visit The Welsh Stone Forum http://www.museumwales.ac.uk/cy/364/